The Evil Within First Look

The lunatics are taking over the asylum in Shinji Mikami’s return to survival horror.

Shinji Mikami looks up from beneath the brim of his trademark cap, which sits low, shielding his eyes.

“Obviously I like horror,” he muses. “But survival horror has been drifting away from what makes it survival horror. And so I want to bring it back. Bring back survival horror to where it was.”

If anyone can restore essence to the genre, Mikami can. The characteristically subdued Resident Evil creator is returning to his old stomping ground with the debut game from his Tokyo-based studio Tango Gameworks, the third-person survival horror The Evil Within. And while the game may not adhere to all the ideals we recognize from the genre’s golden age – which, let’s face it, were shakily defined in the first place - it’s built around Mikami’s own definition of the genre he helped create.

“There are a lot of survival horror games nowadays, but the thing that I want to focus on is having the perfect balance between horror and action.”

That perfect balance, in Mikami’s opinion, is what makes ‘pure’ survival horror.

The Evil Within certainly has the set-up to deliver on Mikami’s promises. Its premise is a cliché, but it would be misleading to suggest the game is; the poster for The Evil Within plastered around the colourful walls of Tango’s office depicts a brain wrapped in barbed wire. It’s in this image that its mental asylum spookhouse setting develops new meaning, one more sinister than the threat of things that go bump in the night.

“Thematically, it’s less about having twists and turns and more about maintaining an air of mystery,” explains Mikami. “So through the story you learn a little bit more, and then a little bit more, but the more you learn, you also realize there’s far more mystery out there to unfold.”

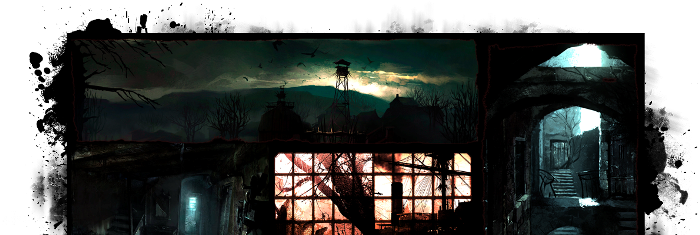

The game’s prologue sets up protagonist Sebastian, a chiselled but otherwise nondescript detective called in to investigate a homicide at an inner-city asylum. He and his colleagues – a man called Joseph and a female detective they simply address as ‘Kid’ – arrive late to the scene. The parking lot is littered with police cars. The asylum, all Gothic architecture, looms. The cars are empty, Sebastian notes. There are no signs of violence but every single car is empty.

Like Mikami’s last foray into the genre, Resident Evil 4, The Evil Within is deeply cinematic, but while RE4 was presented in 16:9 (letterboxed on the GameCube within a 4:3 frame), The Evil Within has a true cinematic 2.35:1 aspect ratio, resulting in a low-sitting camera which displays an enormous amount of the environment at any given time. The camera, naturally, sits over Sebastian’s shoulder.

“We’re paying a lot of attention to the theatrical and cinematic aspects of the game,” says Mikami. "We want the game to be scary so we want to support that throughout the game experience, but we don’t want to go so far as to impact on the flow of gameplay. We want the controls and the way players interact with the controls and the game to feel scary and cinematic, but not cumbersome. So once you get on more of the action elements you want players to focus on that. So you’ll see something of a wave, you’re drifting from one end to the other end – from cinematic elements to purely gameplay elements and back and forth.”

Venturing into the asylum’s vast, high-ceilinged lobby, someone remarks that the place “smells of blood.” Bodies of cops, doctors and patients slump on chairs and against walls. Sebastian makes his way into a video surveillance room, where a wounded doctor mumbles something I half missed (although I have a feeling that was the point), “it was him, it couldn’t be,” perhaps. Peering at the screens, Sebastian sees a hooded figure slaughtering helpless police; suddenly, the figure appears behind Sebastian, and he’s knocked unconscious.

It’s here that The Evil Within proper begins, and I start to gain an understanding of the kind of game Mikami is weaving together: confrontational, gore-soaked and rooted in madness; although whose madness exactly is part of the intrigue. It’s recognizably survival horror, but delivered with a wealth of detailing realized in a heavily modded id Tech 5 engine which Art Director Naoki Katakai (Resident Evil Remake, Okami, Vanquish) calls “Tango-stylized.” We see every spot of blood, every severed intestine with garish clarity; beautifully disgusting.

When Sebastian wakes up, he’s hanging upside down in a meat-locker, the lair of a madman, surrounded by victims of a similar fate. A giant, hulking butcher in a stained wife-beater and apron lumbers in and cuts down one of Sebastian’s hanging fellows, dragging him off to a well-worn butcher’s block to gut him with an indelicate squelch. The scene is immediately otherworldly, a decrepit, blood-splattered alternate asylum lit by a flickering fluorescent bulb, too at odds with the game’s previous environment to be in any way grounded in ‘reality’.

“The mental hospital is a really important key word for us,” says Katakai. “It’s one of the many stages that we have, but it’s one of the more forward facing, symbolic areas. It’s really important to us to design and realize that as a playable area. Visually the sense is that it’s inside of a metropolitan area but it has a feel that it could be urban or maybe rural with some sort of history associated with it. Having said that, through the course of the narrative, it may take on different faces. It may look different ways or have different aspects that come to the fore in depicting what this place is.”

What happens next is a striking example of Mikami’s grasp of tension; Sebastian must avoid the giant in a long, drawn out, silent bid for freedom.

“The way the player moves is very important," explains Mikami. “Obviously you’re going round in this environment, but when there are enemies nearby the character becomes very alert, and that’s when you start sneaking and crouching, you can run as well; but depending on whether there’s monsters out to get you or whether you feel safe, the variety and range of motions change, the animations change.”

It’s when Sebastian accidentally trips an alarm in the corridor that the tension breaks, as the alerted butcher bursts onto the scene brandishing one of Mikami’s trademark weapons, a chainsaw. Our protagonist runs from the encroaching rattle at an awkward gallop, all arms flung behind him, far from graceful. His very human physicality evokes former survival horror everymen – a Harry from Silent Hill or a Leon - and crucially, encourages us to see him as vulnerable.

“It’s much harder to scare players these days,” says Producer Masato Kimura. “We hope to overcome that, or address that by having a more immersive experience, we want you to identify with the protagonist, with the main character, we want you to feel what he feels. When he’s scared we want you to be scared. When he’s excited we want you to have the same feeling. We’re hoping we can address this and represent this in a way you don’t see in other games.”

When the fiend doesn’t know where Sebastian is, its movements are erratic and unpredictable; when it spots him, Sebastian must either run or get a chainsaw to the neck (an outcome that Tango kindly demonstrated for us). It’s tense, so tense that when Tango’s representative tries to demonstrate how Sebastian can interact with his environment by throwing an empty bottle to distract the monster, he screws it up; the bottle smashes against the monster itself and it carries on with its relentless search. The rep curses, and laughs. There’s no hiding now; Sebastian must race to literally save his neck.

Unsurprisingly, this particular sequence ends in a frenzied sprint towards freedom; right after Sebastian leaps into an elevator and safety, the asylum itself begins to crumble around him. He limps past the rusted frames of forgotten gurneys and ancient wheelchairs – the abandoned hospital trope puts us very much in Jacob’s Ladder territory here – runs through the lobby, and opens the door to a devastated cityscape. Police cars lie upside down in a giant crater, and the carnage stretches as far as the eye can see. The prologue ends.

“It’s just my personal opinion,” says Mikami, “but I’m the type of person, I’m the type of creator that when someone says ‘that’s what I do, that’s my personal thing’ I want to do something different. I’ve done a lot of different things; I’ve done a lot of different kinds of games in my career, but really it always comes down to that – I want to overcome people’s perceptions of me.”

Indeed.

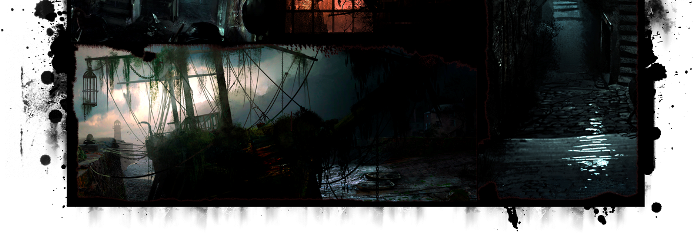

The second half of our demo dumps Sebastian alone in the dark outside as he makes his way towards an old abandoned cottage. There is no context for where he is; it’s a section intended to demonstrate the ‘action’ part of Mikami’s central pillar. We’re yet to see anything on the HUD, save a single sliver of a health bar at the bottom of the screen, but interactive elements are marked with on-screen prompts. Sebastian has a gun: when he draws it, a small weapon icon shows a limited amount of ammo; a gesture of defence, really.

“We’re not giving the player really any extraordinary powers,” says Mikami, "but we don’t want to go in the opposite direction and not give them any means of fighting back – that would violate the rules of survival horror. So we’re looking at appropriate types of weapons with a limited amount of ammunition in order to get them through... if they’re good.”

It’s in this cottage that Sebastian encounters what I can only assume are The Evil Within’s more garden-variety enemies, if such aberrations could be labelled as such. Zombie-like, they shamble towards him with blind bloodlust, but they’re a more unearthly kind of undead; of the first two that Sebastian encounters, one is wrapped in barbed wire, and the other peppered with glass shards. Physical manifestations of their own mental torment, perhaps.

“With most of the enemies in the game,” explains Katakai, “an important design concept is that they are always victims. Even when they’re evil creatures, there are greater evils still that are impacting on them or causing them to suffer.”

Like the asylum, the decrepit cottage presents a very linear, labyrinthine environment, although Katakai promises that the game will open up later on.

“Overall we have both very narrow, confined spaces and larger, wide open spaces – a variety of different types of environments. The idea is to have a wave where the player builds up a lot of tension and feels very claustrophobic and set upon and then they break through that tension and things open up and they feel a sense of relief. Then to repeat that cycle. Also, having narrow stages and having more open stages, it provides more opportunities to have enemies come out in unexpected ways or in unexpected places.”

In this instance, a wave of enemies – moving in a slow and purposeful flock very much in the spirit of Resident Evil 4’s Los Ganados – approach Sebastian from outside. Our Tango representative selects a mine trap from his inventory, which Sebastian lays down by the doors; the rest of them are taken care of via handgun as they try to clamber through the windows. Headshots explode brains with a satisfyingly meaty splat.

Of course, such straightforward run n’ gun gameplay is far too pedestrian for Tango, and it’s here that we are offered a tantalizing glimpse of what Mikami believes will be The Evil Within’s game-changing feature. Without warning, Sebastian’s environment suddenly switches; but not so dramatically that I was sure it wasn’t a glitch, or that I hadn’t, in a split-second, missed something vital. Sebastian traces his steps back, the all-knowing Tango representative mimicking the confusion new players will likely feel. Where did I just come from? What just happened? Where’s the exit? Before we get an answer, a wave of blood tumbles down the corridor and envelops our bewildered protagonist; a set-piece straight out of The Shining. When Sebastian ‘comes to,’ he is back in the asylum.

“It’s a fundamental setting in the game," says Mikami. “It’s what’s going to make the game stand out and really be unique. It’s going to make The Evil Within what it is.”

While Mikami didn’t want to provide context for me for fear of spoilers, he did explain that the inspiration for the strange switches in space came from the infamous

Winchester House, the architectural oddity that was under construction for 38 years under the unhinged eye of Sarah Winchester.

“It has doors that open up and suddenly there’s a dead drop or stairs or something like that. It otherwise looks normal but suddenly things change in an instant and you don’t know what to expect.”

It’s clear that the developers are aiming for a careful balance of not only action and horror, but of the old and the new, weaving classic survival horror tropes with new and interesting psychological horror features. And it’s all wrapped up, of course, in a state-of-the-art package (on both current and next-gen technology), resulting in a game that has that Resident Evil-era Mikami vibe, but feels much, much richer overall.

“15 or 20 years ago, characters in video games were walking around like robots, and the games were very linear, but now you’re able to put in a much greater detail into the character and it really adds to the immersion,” says Mikami.

"You don’t require the player to use their imagination as much as you had to in the past. You’re able to show things on a much more granular level. A much finer level of detail. And make things feel that much more visceral to the player. You’re able to impart a much greater sense of space and able to use lighting to your advantage much more than you were able to in the past.”

Our demonstration ends with a glimpse at a new enemy, which - fittingly - throws up further questions pertaining to the nature of this world and its inhabitants. It's a giant, multi-legged, multi-armed wraith that explodes from a fountain of blood and rushes towards Sebastian at a breakneck clip. As the code resets to the title screen, everyone in the room laughs nervously. It’s an appropriate reaction to such a relentless 25 minutes. While Mikami acknowledges that it’s harder to scare people these days, that laugh says it all.

“Horror as a genre has a set number of patterns, and the more time you spend with those patterns the more you get used to them. And the more used to those patterns a person is, the harder it is to scare them and do something above and beyond and original.”

He lifts up the brim of his cap slightly.

“If players say 'I haven’t played a game this scary in a while,' that would make me the happiest.”

).

).