No opinar diferente no es mentir. Yo creo que se entiende y te voy a poner un ejemplo y espero que los sepas comprender: No hace mucho en otro hilo tu dijiste que los LCD también tienen ABL para mi eso es mentir y creo que sabiendolo a conciencia.

Estás usando un navegador obsoleto. No se pueden mostrar este u otros sitios web correctamente.

Se debe actualizar o usar un navegador alternativo.

Se debe actualizar o usar un navegador alternativo.

OLED LG y sus paneles defectuosos con tara

- Autor calibrador

- Fecha de inicio

No, no mentí cuando dije que los LCD tienen ABL. Quizás no entendiste que me refería EXCLUSIVAMENTE a HDR (no en SDR, donde efectivamente no existe el concepto de limitación de brillo, porque no llegan a más de 400 nits, que es más que asumible).

Como supongo que bien sabrás, un panel que afirme que llega a los 1000 nits en HDR, no lo hace a toda pantalla. Porque existe un LIMITADOR que lo impide. Es más, incluso en areas menores, existe un PICO SOSTENIDO, tras el cual la iluminación baja. Sea en LCD o en OLED. Da igual.

Aquí tienes la prueba de lo que digo, por parte de RTINGS:

Peak Brightness of TVs: Max luminosity and HDR highlights

Ahora, si quieres, me vuelves a decir que miento.

Dicho ésto, te puedo AFIRMAR que el ABL en mi ex 930 era más agresivo que en mi C6, donde nunca lo he visto actuar en contenido REAL

Como supongo que bien sabrás, un panel que afirme que llega a los 1000 nits en HDR, no lo hace a toda pantalla. Porque existe un LIMITADOR que lo impide. Es más, incluso en areas menores, existe un PICO SOSTENIDO, tras el cual la iluminación baja. Sea en LCD o en OLED. Da igual.

Aquí tienes la prueba de lo que digo, por parte de RTINGS:

Automatic brightness limiting is a feature that dims the maximum luminance of the TV when a large portion of the TV is displaying a bright color. This is done to help prevent components used in the TV from being damaged when the TV makes the screen really bright across a wide amount of space.

This is a bigger problem with OLED TVs than it is with LED TVs, but it does affect both. Here is a comparison:

LG EF9500 LG UH8500 Sony X930C

OLED TV LED TV LED TV w/ highlight brightening

2% 346.2 cd/m2 302.7 cd/m2 641.7 cd/m2

10% 345.6 cd/m2 312.9 cd/m2 597.1 cd/m2

25% 349.1 cd/m2 311.4 cd/m2 570.2 cd/m2

50% 219.9 cd/m2 311.4 cd/m2 474.3 cd/m2

100% 126.7 cd/m2 314.8 cd/m2 468.5 cd/m2

You can see that with OLED, the brightness is greatly reduced when the screen is displaying large bright areas. With LED, you don’t have much fluctuation unless you enable a highlight brightening feature.

Overall, even for OLED TVs, this isn't a big issue, and you will probably not notice it unless you are actively looking for it.

Peak Brightness of TVs: Max luminosity and HDR highlights

Ahora, si quieres, me vuelves a decir que miento.

Dicho ésto, te puedo AFIRMAR que el ABL en mi ex 930 era más agresivo que en mi C6, donde nunca lo he visto actuar en contenido REAL

El ABL es un circuito que tienen los OLEDs que limitan o más bien recortan el brillo del contenido porque si lo representasen tal como viene dañaria significativamente el panel. Este circuito no lo tienen los LCDs, en ningún sitio he visto decir esto supongo que será porque son capaces de representar el brillo de cada pixel fiel al contenido sin dañarse. Y por favor no insistas en tratarnos de tontos y vengas a mezclarnos churros con meninas, nits pantalla completa o pantalla del 10 %.

Mira, te he puesto parte de una página de RTINGS donde AFIRMA que tanto OLED como LCD tienen ABL (EN HDR) y te he puesto el enlace, con mediciones en tres televisores. Ahora, haz lo que te plazca con esa información, pero a mí no me acuses de MENTIR, vale?.

Te he dado información MIA de primera mano, diciendote que en mi C6 NUNCA he visto actuar el ABL en contenido REAL. Pero sigue sin valerte y piensas que sigo siendo un mentiroso.

Por lo que veo, tú has entrado aquí a liarla. Así que salvo que vayas a tener una discusión constructiva (y no echar balones fuera diciendo que lo que digo no te vale como argumento), este es mi último mensaje al respecto contigo.

Te he dado información MIA de primera mano, diciendote que en mi C6 NUNCA he visto actuar el ABL en contenido REAL. Pero sigue sin valerte y piensas que sigo siendo un mentiroso.

Por lo que veo, tú has entrado aquí a liarla. Así que salvo que vayas a tener una discusión constructiva (y no echar balones fuera diciendo que lo que digo no te vale como argumento), este es mi último mensaje al respecto contigo.

Bueno yo lo del ABL en un LCD repito que no lo he visto en ningún lado. Bien en esa página efectivamente se dice que los LCDs también lo tienen, pero dice muy bien que es un problema menor. Por favor si puedes decirme en cuantos sitios has visto, del que has aprendido a decir que los LCD sufren de ABL. Tampoco se puede elevar a verdad lo que se vea en una página además que se podría discutir de lo que pone esa página, la manipulación en el periodismo existe. Pasa lo mismo que cuando hablamos que los quemados, en los LCDs también existen, pero la gente no va diciendo que los LCDs es una tecnología cuyo uno de sus problemas sean los quemados y creo que todos los sabemos. Siento la discusión y fin también de la replica por mi parte.

Edgtho

Miembro habitual

Josemay por lo que veo has entrado en el foro como un elefante en una cacharrería. No llegas a los 20 mensajes y estás atacando a uno de los miembros mas antiguos. Pues bien ahora soy yo el que te acusa de mentir, y por omisión.

Por parte de @actpower se puede entender que rtings es una web de referencia, sin embargo a ti de forma mágica no te sirve. Y pides mas referencias. Si te sirve que cuando dicen que el ABL es un problema menor pero omites que se refiere INCLUSO A LOS OLED. La frase textual, que menciona a los OLED y la cual te cito, la conviertes a una mención de que es un problema menor PARA los LCD. Eso si es mentir, y liar, coger solo lo que te interesa y transformarlo para que responda a tu argumento no es la primera vez que lo haces en 20 mensajes, pero si la mas clara.

Y a los que nos interesa leer, formarnos y aprender de estas discusiones técnicas no nos gustan mucho esas actitudes.

Overall, even for OLED TVs, this isn't a big issue, and you will probably not notice it unless you are actively looking for it.

Bien en esa página efectivamente se dice que los LCDs también lo tienen, pero dice muy bien que es un problema menor. Por favor si puedes decirme en cuantos sitios has visto, del que has aprendido a decir que los LCD sufren de ABL.

Por parte de @actpower se puede entender que rtings es una web de referencia, sin embargo a ti de forma mágica no te sirve. Y pides mas referencias. Si te sirve que cuando dicen que el ABL es un problema menor pero omites que se refiere INCLUSO A LOS OLED. La frase textual, que menciona a los OLED y la cual te cito, la conviertes a una mención de que es un problema menor PARA los LCD. Eso si es mentir, y liar, coger solo lo que te interesa y transformarlo para que responda a tu argumento no es la primera vez que lo haces en 20 mensajes, pero si la mas clara.

Y a los que nos interesa leer, formarnos y aprender de estas discusiones técnicas no nos gustan mucho esas actitudes.

Siento decir que yo no soy de los que va idolatrando a personas y a páginas, y la verdad que siempre voy dudando hasta de las de más prestigio tienen. Creo recordar que incluso hay un video de youtube que se acusa de manipulación a Rtings imagino que aquí que estais al tanto de casi todo creo que lo habreis visto, lo he intentado buscar asi rapido y no lo he encontrado, si lo encuentro lo pondré y sino que no sea tenido en cuenta mis palabras. En cualquiera de los casos eso solo es una valoración de una web, una empresa que vive de publicidad y sus lectores son principalmente un perfil de público que todos sabemos no refleja a la ciudadania. Creo que las empresas mayores no se libran de función manipuladora. La verdad que pienso que ir diciendo que los LCDs tienen ABL y sufren de quemados, así a secas sino lo quieres ver como mentira, cada uno que lo vea como lo quiera ver, pero yo lo siento desde mi ignorancia así o casi así lo veo. Yo eso no lo veo decir a la gente, aunque eso no significa que si haya gente que lo diga.

calibrador

Borinot sense trellat

El ABL de toda la vida ha sido como medida de protección de las pantallas, nada relacionado con el consumo. Lo del consumo ha llegado mucho más tarde.

Esto es muy fácil de entender. A la pregunta: ¿Si no existieran normas de restricción de consumo, las OLED tendrían ABL? SÍ, como medida de protección de la propia pantalla, o sea, da igual la normativa, el limitador de brillo automático lo tendrían igualmente.

Esto es muy fácil de entender. A la pregunta: ¿Si no existieran normas de restricción de consumo, las OLED tendrían ABL? SÍ, como medida de protección de la propia pantalla, o sea, da igual la normativa, el limitador de brillo automático lo tendrían igualmente.

calibrador

Borinot sense trellat

Por cierto, el ABL jamás se ha notado en contenido real puesto que no es más que un limitador de brillo automático que no permite a la pantalla pasar de un punto, por lo tanto, no lo notas en la medida de fluctuaciones y tal, simplemente la pantalla en determinadas situaciones jamás alcanzará unos indices de luminancia especificos. No se nota pero está ahí haciendo que la imagen no sea tan brillanta a cómo debería serlo en según qué situaciones.

Edgtho

Miembro habitual

Vamos @josemay que te permites el lujo de dudar y descartar cualquier cosa que no sea refutar tu argumentario, por que tú lo vales, aunque sea manipulando. Y una manipulación clarísima de una cita se convierte en "es que rtings no sirve". Pues vale, creo que lo has terminado de arreglar, poco te voy a leer yo a ti.

No estoy seguro si este es el video del que he visto hablar sobre rtings, pero asi a voz de pronto ver y opinar lo que querais:

Como dije tampoco creo que tenga importancia, pero he intentado en la medida de lo posible cumplir con mi palabra:

Como dije tampoco creo que tenga importancia, pero he intentado en la medida de lo posible cumplir con mi palabra:

Última edición:

Por favor si alguien sabe como se envia un privado a Edgtho se lo agradeceria ya que como no me lee queria decirle que yo estaba hablando sobre el ABL en los LCDs y creo que no he omitido lo que pone en esa página sobre el abl en los lcds. Creo que no estaba hablando ni discutiendo sobre el tema del ABL en los OLEDS. Me gustaria saber su opinión a este respeto. Y no es que me guste dudar de lo que pone en una web que no refuta lo que yo creo que he aprendido porque yo lo valgo sino que pienso que dudar de todo, refute o no tus ideas es bueno. gracias.

calibrador

Borinot sense trellat

calibrador

Borinot sense trellat

Por favor si alguien sabe como se envia un privado a Edgtho se lo agradeceria ya que como no me lee queria decirle que yo estaba hablando sobre el ABL en los LCDs y creo que no he omitido lo que pone en esa página sobre el abl en los lcds. Creo que no estaba hablando ni discutiendo sobre el tema del ABL en los OLEDS. Me gustaria saber su opinión a este respeto. Y no es que me guste dudar de lo que pone en una web que no refuta lo que yo creo que he aprendido porque yo lo valgo sino que pienso que dudar de todo, refute o no tus ideas es bueno. gracias.

Es muy fácil. Pincha sobre el avatar y después iniciar una charla. Aquí los mp se llaman charlas

Lo del ABL está muy claro. en SDR se dice que una TV tiene ABL cuando el brillo máximo recomendado por la industria de 120 nits, el TV solo lo alcanza en un patter ventana, y después al pasar a ventana completa el brillo se ve reducido, ahí existe, por una u otra razon, ABL. En principio era para proteger las pantallas y después con la normativa a los fabricantes les vino a huevo para echarle la culpa a las leyes, cuando mucho antes ya aplicaban mecanismos ABL en sus pantallas para su correcto funcionamiento y protección. Esto es así de simple.

Pero con las nuevas especificaciones para alto rango dinámico HDR, la cosa cambia, porque hay que alcanzar brillos máximos mayores, por ejemplo 1000 nits. Pero aqui los organismos ya indican que solo ha de hacerlo la pantalla en un porcentaje pequeño del 10%, o sea, a diferencia de SDR aquí ya no hace falta que el brillo ocupe toda la pantalla. Por esa razón las pantallas LCD en HDR llevan ABL, porque no hace falta alcanzar esos niveles de brillo a pantallla completa, solo en un área muy pequeña.

¿Para qué van a soltar 1000 nits a pantalla completa si no es necesario y no se contempla en las especificaciones? Pues para nada porque no es necesario, de ahí el ABL en las LED.

Pero esto ni es por el consumo ni por proteger las pantallas LED, es simplemente porque no se contempla en las especificaciones y además sería absurdo tanto brillo.

En las OLED es distinto, porque independientemente de las leyes de restricción y la norma que dice que solo en un 10% de patrón ventana, sino tuvieran un limitador de brillo automático ABL cascarían, o sea, este mecanismo es necesario para la protección de la pantalla OLED y su correcto funcionamiento independientemente de las leyes y las normas.

En definitiva. Basicamente estoy de acuerdo con lo que has expuesto con matices

Última edición:

Gracias Ronda le he mandando un privado a Edghto diciéndole que yo estaba hablando sobre el ABL en los LCDs y no sobre el ABL en los OLEDS, ni en una comparativa sobre el ABL en los LCDS y OLEDS. Por tanto no omiti nada de lo que se hablaba en ese artículo referente al ABL de los LCDs, es más admití que en la página efectivamente se decia que los LCDS tienen ABL, pero la verdad no me parecia del todo creible porque yo no lo he visto decir nunca y he vista bastantes páginas al respecto. Le he dicho que agradeceria su respuesta.

Ronda ya lo dije anteriormente que en HDR los expertos se fijan en el brillo alcanzado en una ventana del 10 %. Aquí está mi mensaje donde lo dije: OLED: el post | Página 76 | NosoloHD . En el mismo mensaje dije que decir que los LCDs no alcanzan 1000 nits a pantalla completo no sirve para nada porque no es necesario. Efectivamente los LCDs no alcanzan 1000 nits a pantalla completo, pero no lo necesitan. Hombre decir que en los LCDS hay ABL me sigue pareciendo que es incorrecto, porque yo creo que todos entendemos que el ABL es un limitador de brillo que hace que el brillo del contenido no sea visualizado en el televisor para proteger a la pantalla y sigo pensando que eso en los LCDs no ocurre, y aunque parezca un poco pesado me remito que yo no había visto decirlo en ninguna página que tampoco tiene porque ser prueba refutable, al igual que no es refutable que lo ponga en una página por eso lo discutimos.

Gracias por todo.

Ronda ya lo dije anteriormente que en HDR los expertos se fijan en el brillo alcanzado en una ventana del 10 %. Aquí está mi mensaje donde lo dije: OLED: el post | Página 76 | NosoloHD . En el mismo mensaje dije que decir que los LCDs no alcanzan 1000 nits a pantalla completo no sirve para nada porque no es necesario. Efectivamente los LCDs no alcanzan 1000 nits a pantalla completo, pero no lo necesitan. Hombre decir que en los LCDS hay ABL me sigue pareciendo que es incorrecto, porque yo creo que todos entendemos que el ABL es un limitador de brillo que hace que el brillo del contenido no sea visualizado en el televisor para proteger a la pantalla y sigo pensando que eso en los LCDs no ocurre, y aunque parezca un poco pesado me remito que yo no había visto decirlo en ninguna página que tampoco tiene porque ser prueba refutable, al igual que no es refutable que lo ponga en una página por eso lo discutimos.

Gracias por todo.

Edgtho

Miembro habitual

Mira, te voy a explicar un par de cositas: la primera es que existe un procedimiento de ignorados pero muy poquita gente lo usa. Si yo te pusiera en ignorados serviría de poco que me enviaras una charla, esta no podría leerla.

Segunda, cuando te dije que no iba a leerte me refería a que nada de lo que digas lo tomaré en cuenta ¿Y sabes por qué? Por que puedes ser la ostia, ser un pedazo de entendido y mil cosas, pero por tus formas me pareces un charlatán. Uno de estos que se rodean de datos técnicos y que se dan una sobreimportancia que no merecen para estar siempre por encima de los demás. Y te digo una cosa: soy analista programador, estoy continuamente en las empresas y parte de mi trabajo es poder clasificar a la gente.

Ahora resulta que "solo" hablabas del abl en los LCD.... vuelves a mentir por omisión, si es que sabes lo que significa.

Segunda, cuando te dije que no iba a leerte me refería a que nada de lo que digas lo tomaré en cuenta ¿Y sabes por qué? Por que puedes ser la ostia, ser un pedazo de entendido y mil cosas, pero por tus formas me pareces un charlatán. Uno de estos que se rodean de datos técnicos y que se dan una sobreimportancia que no merecen para estar siempre por encima de los demás. Y te digo una cosa: soy analista programador, estoy continuamente en las empresas y parte de mi trabajo es poder clasificar a la gente.

Ahora resulta que "solo" hablabas del abl en los LCD.... vuelves a mentir por omisión, si es que sabes lo que significa.

Edgtho desconocia que los mensajes de ignorados tampoco llegasen. Lo siento.

No comparto tus descalificaciones y acusaciones, pero bueno ahí están. Y por último vuelvo a insistir que en el mensaje de la discordia que creo es este: OLED LG y sus paneles defectuosos con tara | Página 8 | NosoloHD yo solo hable del ABL en los LCD. Creo que lo podeis comprobar.

No se me caen los anillos por rectificar que he dicho una cosa incorrecta, o lo que podría tratarse de una mentira que habría que ver si fue intensionada o por no darme cuenta, ya lo hice anteriormente en este mensaje: DOLBY VISION (EL HDR PREMIUM) | Página 2 | NosoloHD

No comparto tus descalificaciones y acusaciones, pero bueno ahí están. Y por último vuelvo a insistir que en el mensaje de la discordia que creo es este: OLED LG y sus paneles defectuosos con tara | Página 8 | NosoloHD yo solo hable del ABL en los LCD. Creo que lo podeis comprobar.

No se me caen los anillos por rectificar que he dicho una cosa incorrecta, o lo que podría tratarse de una mentira que habría que ver si fue intensionada o por no darme cuenta, ya lo hice anteriormente en este mensaje: DOLBY VISION (EL HDR PREMIUM) | Página 2 | NosoloHD

Lo del ABL está muy claro. en SDR se dice que una TV tiene ABL cuando el brillo máximo recomendado por la industria de 120 nits, el TV solo lo alcanza en un patter ventana, y después al pasar a ventana completa el brillo se ve reducido, ahí existe, por una u otra razon, ABL. En principio era para proteger las pantallas y después con la normativa a los fabricantes les vino a huevo para echarle la culpa a las leyes, cuando mucho antes ya aplicaban mecanismos ABL en sus pantallas para su correcto funcionamiento y protección. Esto es así de simple.

Pero es que practicamente ningún propietario de TV va a calibrar una OLED o una LCD a 120cd/m2. Que sí, que eso es lo que te indica "la industria", pero salvo cuatro que sigan esa norma, todos hacen lo que se ha hecho SIEMPRE: Subir contraste al máximo (ergo más blanco intenso) y ajustar brillo (esto a ojímetro, claro).

Con patrones da la casualidad que el Contraste en las OLED sube prácticamente al 100 (yo lo tengo en 96). ¿Y sabes qué sucede?. Pues que obtienes más de 120cd/m2 en patrones (pero mucho más). Y el ABL en mi televisor no lo he visto actuar de momento.

Pero si quieres evitarlo, hay una forma fácil que un usuario descubrió: Bajas contraste a 60 y subes luz OLED a 100 (compensando así la bajada de luz producida por el contraste). Dado que la luz OLED afecta más a los pixeles que más se iluminan y NO a lo más oscuros/negros, y el ABL no afecta sobre la luz OLED, se asegura uno de que al menos si se pone una imagen blanca en toda la pantalla no se pegue el bajón de luminosidad.

Pero insisto, un "Fade to White" en una peli, NO hará que actúe el ABL, el pico de luz seguirá estando ahí el tiempo suficiente para que se note. Ergo, da igual que el ABL actúe, porque NO lo hace bajo esas condiciones. Eso es lo que YO he observado repetidamente.

El ABL en los OLED solo actúa cuando pones un blanco que llene toda la pantalla o una imagen fija con mucho brillo (nieve, por ejemplo). A poco que haya movimiento, NO actúa, porque las condiciones de luminosidad van cambiando y aunque a veces se llegue al límite, las OLED actuales están más preparadas a ese respecto.

Es cuestión de saber configurar el aparato, claro. Si pones modo vivos, subes luz oled al máximo y contraste al máximo, te aseguro que eso no lo aguanta NI CRISTO y vas a ver ABL constantemente. Claro que sí. ¿Pero a quién se lo ocurriría ponr esos settings?. Pues alguno habrá, FIJO.

Pero con las nuevas especificaciones para alto rango dinámico HDR, la cosa cambia, porque hay que alcanzar brillos máximos mayores, por ejemplo 1000 nits. Pero aqui los organismos ya indican que solo ha de hacerlo la pantalla en un porcentaje pequeño del 10%, o sea, a diferencia de SDR aquí ya no hace falta que el brillo ocupe toda la pantalla.

¿Qué organismos, puedes poner la fuente de esa afirmación?. Yo puedo generarte una imagen (NO UN PATRÓN) que llegue a los 4000 nits si quiero, ocupando más del 70% de la imagen. Es obvio que el circuito ABL de los LCD y OLED (EN HDR) actuará, porque están diseñados para eso, pero no lo verás actuar en un Pulsar o en el BVMX300 de Sony.

Lo que sí hay un CONSENSO entre coloristas PROFESIONALES y en general en la industria, una especie de pacto no firmado en el que se comprometen a no generar imágenes de más nits de los aconsejados en un área de imagen muy grande, precisamente porque te pueden dejar medio ciego (y el riesgo de epilepsia es mayor, no es algo para tomárselo a broma).

Cuando tengamos displays que lleguen a 4000 nits vamos a sufrir los verdaderos problemas con los que pasan de normas y de rollos. Eso es lo que más me preocupa...gente en su casa realizando contenidos "out of specs" que sobrepasarán con mucho lo admisible.

Resumiendo, el ABL está diseñado para múltiples objetivos, no por uno en concreto. Pero yo, o no me hago entender, o tengo que estar demostrando constantemente mis afirmaciones, y cansa mucho tener que andar con "papelitos demostrativos" como en la Administración Pública, coño.

El que quiera saber, que busque información DE VERDAD, de gente que SABE, no de foros raros de gente que cree que sabe leyendo a Xataka y mierdas así.

Y un buen sitio donde empezar es Lift Gamma Gain - The Colorist & Color Grading Forum , lejos de foros tipo AVSForums y tal, donde hay más aficionados que profesionales.

calibrador

Borinot sense trellat

Lo del ABL está muy claro. en SDR se dice que una TV tiene ABL cuando el brillo máximo recomendado por la industria de 120 nits, el TV solo lo alcanza en un patter ventana, y después al pasar a ventana completa el brillo se ve reducido, ahí existe, por una u otra razon, ABL. En principio era para proteger las pantallas y después con la normativa a los fabricantes les vino a huevo para echarle la culpa a las leyes, cuando mucho antes ya aplicaban mecanismos ABL en sus pantallas para su correcto funcionamiento y protección. Esto es así de simple.

Pero es que practicamente ningún propietario de TV va a calibrar una OLED o una LCD a 120cd/m2. Que sí, que eso es lo que te indica "la industria", pero salvo cuatro que sigan esa norma, todos hacen lo que se ha hecho SIEMPRE: Subir contraste al máximo (ergo más blanco intenso) y ajustar brillo (esto a ojímetro, claro).

Con patrones da la casualidad que el Contraste en las OLED sube prácticamente al 100 (yo lo tengo en 96). ¿Y sabes qué sucede?. Pues que obtienes más de 120cd/m2 en patrones (pero mucho más). Y el ABL en mi televisor no lo he visto actuar de momento.

Pero si quieres evitarlo, hay una forma fácil que un usuario descubrió: Bajas contraste a 60 y subes luz OLED a 100 (compensando así la bajada de luz producida por el contraste). Dado que la luz OLED afecta más a los pixeles que más se iluminan y NO a lo más oscuros/negros, y el ABL no afecta sobre la luz OLED, se asegura uno de que al menos si se pone una imagen blanca en toda la pantalla no se pegue el bajón de luminosidad.

Pero insisto, un "Fade to White" en una peli, NO hará que actúe el ABL, el pico de luz seguirá estando ahí el tiempo suficiente para que se note. Ergo, da igual que el ABL actúe, porque NO lo hace bajo esas condiciones. Eso es lo que YO he observado repetidamente.

El ABL en los OLED solo actúa cuando pones un blanco que llene toda la pantalla o una imagen fija con mucho brillo (nieve, por ejemplo). A poco que haya movimiento, NO actúa, porque las condiciones de luminosidad van cambiando y aunque a veces se llegue al límite, las OLED actuales están más preparadas a ese respecto.

Es cuestión de saber configurar el aparato, claro. Si pones modo vivos, subes luz oled al máximo y contraste al máximo, te aseguro que eso no lo aguanta NI CRISTO y vas a ver ABL constantemente. Claro que sí. ¿Pero a quién se lo ocurriría ponr esos settings?. Pues alguno habrá, FIJO.

Pero con las nuevas especificaciones para alto rango dinámico HDR, la cosa cambia, porque hay que alcanzar brillos máximos mayores, por ejemplo 1000 nits. Pero aqui los organismos ya indican que solo ha de hacerlo la pantalla en un porcentaje pequeño del 10%, o sea, a diferencia de SDR aquí ya no hace falta que el brillo ocupe toda la pantalla.

¿Qué organismos, puedes poner la fuente de esa afirmación?. Yo puedo generarte una imagen (NO UN PATRÓN) que llegue a los 4000 nits si quiero, ocupando más del 70% de la imagen. Es obvio que el circuito ABL de los LCD y OLED (EN HDR) actuará, porque están diseñados para eso, pero no lo verás actuar en un Pulsar o en el BVMX300 de Sony.

Lo que sí hay un CONSENSO entre coloristas PROFESIONALES y en general en la industria, una especie de pacto no firmado en el que se comprometen a no generar imágenes de más nits de los aconsejados en un área de imagen muy grande, precisamente porque te pueden dejar medio ciego (y el riesgo de epilepsia es mayor, no es algo para tomárselo a broma).

Cuando tengamos displays que lleguen a 4000 nits vamos a sufrir los verdaderos problemas con los que pasan de normas y de rollos. Eso es lo que más me preocupa...gente en su casa realizando contenidos "out of specs" que sobrepasarán con mucho lo admisible.

Resumiendo, el ABL está diseñado para múltiples objetivos, no por uno en concreto. Pero yo, o no me hago entender, o tengo que estar demostrando constantemente mis afirmaciones, y cansa mucho tener que andar con "papelitos demostrativos" como en la Administración Pública, coño.

El que quiera saber, que busque información DE VERDAD, de gente que SABE, no de foros raros de gente que cree que sabe leyendo a Xataka y mierdas así.

Y un buen sitio donde empezar es Lift Gamma Gain - The Colorist & Color Grading Forum , lejos de foros tipo AVSForums y tal, donde hay más aficionados que profesionales.

Claro, claro, si estamos más o menos de acuerdo.

Sobre qué organismo creo que para las certificación UltraHD premium se indica que una pantalla LED solo ha de alcanzar los 1000 nits en un área de pantalla creo del 10%. A partir de ahí que lleve un ABL que controle el brillo máximo más allá de ese porcentaje de pantalla lo veo de lo más normal, ya que al fin y al cabo la pantalla no va a necesitar un rendimiento lumínico por encima de eso. O sea, sí que hay un ABL.

Además no querremos que una pantalla suelte dos millon s de nits, habrá que poner un límite en alguna parte. Es más, en una LED Edge Led puede ser hasta contraproducente porque mucho brillo arruina el contraste porque el negro se levanta. Por ejemplo, mi Sony llega a 1000 nits en un área inferior al 10% y en determinadas escenas oscuras la imagen se resiente

Creo que en este sentido el fabricante ha de jugar con alcanzar los valores de brillo de la certificación y a la vez mantener un contraste óptimo, cosa que no es nada fácil en una tele Edge Led

Yo creo que los dos tenéis parte de razón y que todo ha sido un malentendido

Ronda, que no me vale el "creo", que me vale un PAPER que diga explicitamente ésto.

Dime si en alguno de estos aparece ALGO al respecto de ello:

https://spaces.hightail.com/space/nEaXy

Ya te digo yo que NO. Porque a poco que leas el foro que he recomendado leer (yo llevo meses leyendo ahí, de tapadillo), encontrarás información de PRIMERA MANO, de la gente que HACE lo que luego tú VES. Y esos sí que controlan a un nivel que ni yo mismo puedo llegar ni llegaré nunca.

Que hay ABL es de cajón. Lo gracioso es que se me acuse de mentir. Ojo, que no te acuse a ti también de mentir. Todos mentirosos, vamos xD

Pero que en monitores profesionales NO hay ABL, es de cajón también. Por eso entre los "pros" se advierten que ojito con el ABL si masterizas directamente con estos televisores. Y que siempre hay que tenerlo en cuenta. SIEMPRE.

Dime si en alguno de estos aparece ALGO al respecto de ello:

https://spaces.hightail.com/space/nEaXy

Ya te digo yo que NO. Porque a poco que leas el foro que he recomendado leer (yo llevo meses leyendo ahí, de tapadillo), encontrarás información de PRIMERA MANO, de la gente que HACE lo que luego tú VES. Y esos sí que controlan a un nivel que ni yo mismo puedo llegar ni llegaré nunca.

Que hay ABL es de cajón. Lo gracioso es que se me acuse de mentir. Ojo, que no te acuse a ti también de mentir. Todos mentirosos, vamos xD

Pero que en monitores profesionales NO hay ABL, es de cajón también. Por eso entre los "pros" se advierten que ojito con el ABL si masterizas directamente con estos televisores. Y que siempre hay que tenerlo en cuenta. SIEMPRE.

calibrador

Borinot sense trellat

Pero la certificación uhd premium no dice que una pantalla LED solo ha de alcanzar para obtener dicha certificación los 1000 nits en solo un área reducida de pantalla?

Sino es así en ese caso yo estaría equivocado, lo admito

Sino es así en ese caso yo estaría equivocado, lo admito

Sierra

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 237

- Reacciones

- 140

Precisamente estaba leyendo un artículo sobre HDR enfocado en el grading y desde el punto de vista de un colorista y comenta esto sobre el ABL en monitor de estudio y como afecta:

HDR, Resolve, and Creative Grading | Alexis Van Hurkman –– Creating and Finessing

Automatic Brightness Limiting (ABL)

There’s one other wrinkle. Consumer HDR displays have legally mandated (regulated by the California Energy Commission and by similar European agencies) limits on the maximum power that televisions can use in relation to their size and resolution. Consequently, automatic brightness limiting (ABL) circuits are a common solution manufacturers use to limit power consumption to acceptable and safe levels for home use. Practically speaking, an ABL circuit limits the percentage of the picture that may reach peak luminance without automatically dimming the display. This type of ABL limiting is not required on professional displays, but some manner of limiting may still be used to protect the display from damage stemming from drawing more current than they can handle in exceptionally bright scenes.

Naturally, on my first HDR grading job I was keenly interested in just how much of the picture could go into very-bright HDR levels before the average consumer HDR-capable TV would interfere, since I didn’t want to push things too far. Unfortunately, nobody could tell me what that threshold was at the time, so I simply proceeded with caution, grading relative to the 30″ Sony BVM X300 display we were using as our HDR reference display (and a beautiful monitor it is). The grade went well, I tried to be judicious about how far I pushed the brightest of the signal levels, and the client went away with a master that made them happy (sadly, it was a secret project…).

Later, I had the good fortune of speaking with Gary Mandle, of Sony Professional Solutions, who illuminated the topic of how ABL affects the HDR image, at least so far as the BVM X300 is concerned. A number of different rules are followed, all of which interact with one another:

Long story short, how ABL gets triggered is complicated, and while you can keep track of how much of the image you’re pushing into HDR-specific highlights, how bright those highlights are, and how clustered or scattered the highlights happen to be, there will still be unknowable interactions at work. Fortunately, the Sony BVM X300 has an “Over Range indicator” light, which illuminates and turns amber whenever ABL is triggered, so you know what’s happening and can back off if necessary. Incidentally, it’s worth noting that the X300, being an OLED display, is susceptible to screen burn-in if you leave bright levels on-screen for too long, so don’t leave an HDR image on pause going out to your display before going home for the evening.

- In general, only 10% of the overall image may reach the X300’s peak brightness of 1000 nits (assuming the rest of the signal is back down at 100 nits or under)

- The overall image is evaluated to determine the allowable output. An extremely simple (and certainly oversimplified) example is that you could (probably) have 20% of the signal at 500 nits, rather than 10% at 1000 nits. I have no idea if this kind of tradeoff is linear, so the truth undoubtedly varies. The general idea is that if you only had, say 2% of the image at 1000 nits, and 5% of the image at 500 nits, then you can probably have a reasonable additional percentage of the image at 200 nits, which is by no means at the top of the range, but is still twice as bright as SDR (standard dynamic range) images that peak at 100 nits. I don’t know what the actual numbers are, but the basic idea is the total percentage of pixels of HDR-strength highlights you’re allowed to have depends on the intensity of those pixels.

- The dispersion of image brightness over the area of the screen is also evaluated, and output intensity is managed so that areas with a lot of brightness don’t overheat the OLED panel.

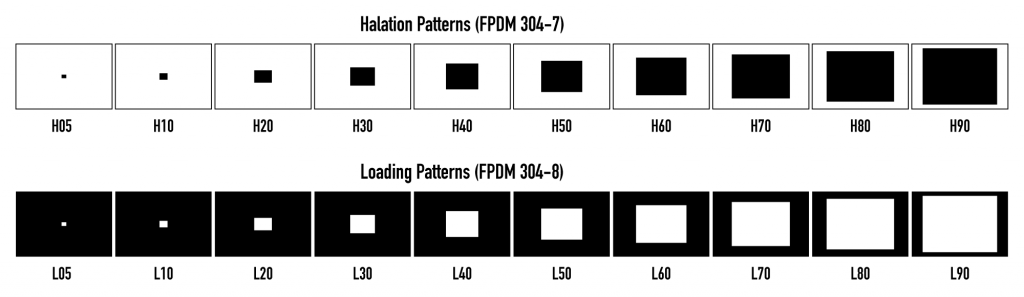

Bram Desmet, CEO of Flanders Scientific, pointed out that VESA publishes a set of test patterns (ICDMtp-HL01) devised by the International Committee for Display Metrology (ICDM) which can be used to analyze a display’s (a) susceptibility to halation, defined as “the contamination of darks with surrounding light areas,” and (b) susceptibility to power loading, which describes screens “that cannot maintain their brightest luminance at full screen because of power loading.” The set consists of two groups of ten test patterns. Black squares against white backgrounds are used to measure halation, while white squares against black backgrounds are used to measure power loading. For the power loading patterns, the ten patterns feature progressively larger white squares against a black background labeled as L05 to L90; the number indicates what diagonal percentage of the screen each box represents (which I’m told is different from a simple percentage of total pixels).

By measuring a display’s actual peak luminance while outputting progressively larger white boxes on black backgrounds, you can determine the maximum percentage of screen pixels that are possible to display at full strength before peak luminance is reduced due to power limiting. Of course, this doesn’t account for all the factors that trigger ABL, but it does provide at least one comprehensible metric for display performance, and some display manufacturers cite one of these test patches as an indication of a particular display’s performance.

Of course, the ABL on consumer televisions is potentially another thing entirely, as each manufacturer will have their own secret sauce for how to handle excess HDR brightness that exceeds a given television’s power limits. Hopefully, consumer ABL will be close enough to the response of professional ABL that we colorists won’t have to worry about it too much, but this will be an area for more exploration as time goes on and more models of HDR televisions become available.

(Update) In fact, I had just published this article when I had to run over to Best Buy to purchase a video game for a friend who I’ve decided is entirely too productive with their time. While I was there, I had a look at the televisions, and in the course of chatting about all of this (because I can’t stop), associate Mason Marshall pointed out a chart at rtings.com that does the kind of test chart evaluation I mention previously to investigate the peak luminance performance of different displays as they output different percentages of maximum white. The results are, ahem, illuminating. For example, while the Samsung KS9500 outputs a startling 1412 nits when 2% of the picture is at maximum white, peak luminance drops to 924 nits with 25% of the picture at maximum white, and it drops further down to 617 nits with 50 percent of the picture at maximum white. Results of different displays vary widely, so check out their chart. Now, this simple kind of Loading Pattern test isn’t going to account for all the variables that a display’s ABL contends with, but it does show the core principal in action of which colorists need to beware.

Dire as all this may sound, don’t be discouraged. Keep in mind that, at least for now, HDR-strength highlights are meant to be flavoring, not the base of the image. My experience so far has been if you’re judicious with your use of very-bright HDR-strength highlights, you’ll probably be relatively safe from the ravages of ABL, at least so far as the average consumer is concerned. Hopefully as technology improves and brighter output is possible with more efficient energy consumption, these issues will become less of a consideration. For now, however, they are.

HDR, Resolve, and Creative Grading | Alexis Van Hurkman –– Creating and Finessing

Pero la certificación uhd premium no dice que una pantalla LED solo ha de alcanzar para obtener dicha certificación los 1000 nits en solo un área reducida de pantalla?

Sino es así en ese caso yo estaría equivocado, lo admito

Esto es lo que dice al respecto:

The UHD Alliance supports various display technologies and consequently, have defined combinations of parameters to ensure a premium experience across a wide range of devices. In order to receive the UHD Alliance Premium Logo, the device must meet or exceed the following specifications:

• Image Resolution: 3840×2160

• Color Bit Depth: 10-bit signal

• Color Palette (Wide Color Gamut)

• Signal Input: BT.2020 color representation

• Display Reproduction: More than 90% of P3 colors

• High Dynamic Range

• SMPTE ST2084 EOTF

• A combination of peak brightness and black level either:

• More than 1000 nits peak brightness and less than 0.05 nits black level

OR

• More than 540 nits peak brightness and less than 0.0005 nits black level

No veo nada donde diga si esos 1000 nits sean sobre un porcentaje específico. Sacado de la propia WEB de la UHD Alliance, vamos.

Respecto a lo que pone Sierra, me quedo con ESTO:

Consumer HDR displays have legally mandated (regulated by the California Energy Commission and by similar European agencies) limits on the maximum power that televisions can use in relation to their size and resolution. Consequently, automatic brightness limiting (ABL) circuits are a common solution manufacturers use to limit power consumption to acceptable and safe levels for home use

Igual poniendolo en NEGRITA y un poco más grande se entiende mejor. ¿Quién miente?. Igual habría que preguntar a ese tipo de donde saca la información pero es que es todo tan, tan claro que...mejor me callo.

calibrador

Borinot sense trellat

Pero la certificación uhd premium no dice que una pantalla LED solo ha de alcanzar para obtener dicha certificación los 1000 nits en solo un área reducida de pantalla?

Sino es así en ese caso yo estaría equivocado, lo admito

Esto es lo que dice al respecto:

The UHD Alliance supports various display technologies and consequently, have defined combinations of parameters to ensure a premium experience across a wide range of devices. In order to receive the UHD Alliance Premium Logo, the device must meet or exceed the following specifications:

• Image Resolution: 3840×2160

• Color Bit Depth: 10-bit signal

• Color Palette (Wide Color Gamut)

• Signal Input: BT.2020 color representation

• Display Reproduction: More than 90% of P3 colors

• High Dynamic Range

• SMPTE ST2084 EOTF

• A combination of peak brightness and black level either:

• More than 1000 nits peak brightness and less than 0.05 nits black level

OR

• More than 540 nits peak brightness and less than 0.0005 nits black level

No veo nada donde diga si esos 1000 nits sean sobre un porcentaje específico. Sacado de la propia WEB de la UHD Alliance, vamos.

Respecto a lo que pone Sierra, me quedo con ESTO:

Consumer HDR displays have legally mandated (regulated by the California Energy Commission and by similar European agencies) limits on the maximum power that televisions can use in relation to their size and resolution. Consequently, automatic brightness limiting (ABL) circuits are a common solution manufacturers use to limit power consumption to acceptable and safe levels for home use

Igual poniendolo en NEGRITA y un poco más grande se entiende mejor. ¿Quién miente?. Igual habría que preguntar a ese tipo de donde saca la información pero es que es todo tan, tan claro que...mejor me callo.

Hombre, yo es que tengo el culo pelao de leer en numerosas REVIEW que los 1000 nits que se le exige a la tecnología LED solo son necesarios en un área pequeña de la pantalla, algo así al 10%.

Si no he buscado la información que lo refleje ha sido porque lo tengo tan claro que ni me voy a molestar en buscar. El que quiera que lo busque porque a mí al fin y al cabo me da igual...

Y sobre los limites de energía antes de que fueran regulados por esa Comisión de Energía de California y las agencias europeas y/o similares, pregunto, entonces por qué las plasmas y CRT tenían ABL antes de establecerse dichas normativas de restricción?

Los límites energéticos no son nada novedoso, los conozco desde la época de las Panasonic viera VT20 haya por el 2010/11, pero hay más, no solo está el ABL para cumplir con los límites energéticos, también para el buen funcionamiento y protección de las pantallas, de hecho todas las Kuro llevaban ABL y son anteriores al establecimiento de esas normativas, y eran pantallas con mejores componentes y fuente de alimentación de lo que llevan las OLED de hoy, de largo.

Es curioso porque por aquella época el gobernador de California era Schwarzenegger. Si el jodio se hubiera impuesto también límites en el uso de ciertas sustancias igual no hubiera llegado hasta donde llegó. Ironías de la vida jajajaja

calibrador

Borinot sense trellat

De todas formas en tan simple como obvio. Si los 1000 nits para LED de la certificación ultra premium se exigiera a tuta pantalla, sencillamente a día de hoy no existiría ninguna LED con certificación uhd premium, y ya hay unas cuantas certificadas que es algo que no concede el fabricante...