Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Se debe tener en cuenta: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Estás usando un navegador obsoleto. No se pueden mostrar este u otros sitios web correctamente.

Se debe actualizar o usar un navegador alternativo.

Se debe actualizar o usar un navegador alternativo.

Crionica, inmortalidad y transhumanismo

- Autor Pereirano

- Fecha de inicio

Pereirano

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 9.218

- Reacciones

- 3.459

IS GETTING OLD A DISEASE?

DRUG RESEARCHERS ARE TRYING TO CONVINCE THE FDA THAT THE ANSWER IS YES

http://www.popsci.com/getting-old-disease

DRUG RESEARCHERS ARE TRYING TO CONVINCE THE FDA THAT THE ANSWER IS YES

http://www.popsci.com/getting-old-disease

Pereirano

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 9.218

- Reacciones

- 3.459

SU CAMPAÑA REIVINDICA LA CIENCIA PARA VENCER LA MUERTE

Zoltan Istvan, el primer transhumanista en la carrera por la Casa Blanca

Zoltan Istvan aspira a convertirse en el primer presidente transhumanista de EEUU. Pretende recorrer el país concienciando sobre la necesidad de combatir la muerte mediante la ciencia y la tecnología

Un ataúd de 12 metros de largo, adornado con una tradicional corona floral, recorrerá los Estados Unidos sobre ruedas. Por fortuna, el féretro no albergará el cadáver de ningún adinerado excéntrico con deseos de innovar en el negocio de las funerarias aprovechando su último desplazamiento. La caja mortuoria se pondrá en marcha en septiembre con un propósito bien distinto: promocionar las ventajas de invertir en ciencia y tecnología para alcanzar la vida eterna.

El viaje contra el envejecimiento y la muerte que emprenderá este siniestro autobús es un proyecto del filósofo, escritor, exreportero del National Geographic y líder del Partido Transhumanista de Estados Unidos Zoltan Istvan. "Un ataúd era un poderoso y excelente símbolo del mayor miedo de mucha gente: tener que morir. Y el principal objetivo de los transhumanistas es superar la muerte gracias a la ciencia, así que un ataúd era un buen emblema", explica a Teknautas.

Hace unos meses, Istvan comenzó una campaña para presentarse comocandidato presidencial a la Casa Blanca en las elecciones de 2016, y ahora ha decidido emprender este road trip de la inmortalidad para reclamar de una forma original un debate sobre el derecho de los ciudadanos a retrasar su propia defunción.

Transhumanistas y robots, unidos por la vida eterna

Este filósofo reconvertido en político quiere conseguir financiación para comprar el autobús que se convertirá en féretro, así que ha lanzado una campaña en Indiegogo en busca de activistas y voluntarios que quieran apoyar su causa o incluso acompañarle en su viaje. Sus mecenas recibirán su eterna gratitud, un ebook con todos los detalles de la aventura o su novela The Transhumanist Wager (La Apuesta Transhumanista), entre otros obsequios.

En el momento de escribir estas líneas, Istvan ha logrado recaudar más de la mitad de los 25.000 dólares (casi 23.000 euros) que necesitaba para que el vehículo esté perfectamente equipado. Pese a su aspecto funerario, dispondrá de la más puntera tecnología en su interior.

Drones, un robot interactivo, equipos de realidad virtual, cámaras para grabar la experiencia y retransmitirla en directo o un laboratorio de biohacking para que los fans de experimentar con su cuerpo se entretengan serán algunos de los atractivos que viajarán a bordo de este autobús de la inmortalidad.

Istvan nos cuenta que los activistas contarán con microchips RFID listos para implantar en su cuerpo, además del instrumental necesario para colocarse imanes bajo los dedos y presumir de la capacidad de atraer objetos metálicos.

"El autobús atraerá a multitud de personas, pero debemos usar nuestras razones para convencer a la gente", señala Istvan. Ahora bien, ¿no es el periplo de este féretro un ejemplo de publicidad engañosa? ¿Podrá Istvan cumplir su ambiciosa promesa política de alargar nuestra vida si llega a presidente de los Estados Unidos?

Según este transhumanista, habrá tres posibilidades para superar la muerte: ralentizar la decadencia humana (los científicos ya han logrado revertir elenvejecimiento de los ratones), dejar que nuestra conciencia se traslade a una máquina o reemplazar aquellas partes de nuestro cuerpo que se vayan quedando inservibles por otros miembros y órganos artificiales, comocorazones robóticos. "Estamos seguros de que la inmortalidad será alcanzable en el futuro", afirma Istvan.

Una Carta de Derechos de los Cíborgs rumbo al Capitolio

Si todavía dudas entre recorrer la ruta 66 por tu cuenta o viajar por Estados Unidos rodeado de transhumanistas durante cuatro meses, has de saber que las paradas de este trayecto para combatir nuestra defunción son cuanto menos curiosas. La aventura comenzará en la costa oeste con el fin de celebrar un evento en cada estado. Istvan quiere organizar un acto en elcampus de Microsoft en Redmond, cerca de Seattle, charlas sobre la longevidad en Phoenix y un trayecto por las cercanías del río Mississippi para denunciar la contaminación de la naturaleza.

La excursión también transitará por el llamado cinturón bíblico de Estados Unidos, al sur del país, para reflexionar sobre la necesaria coexistencia en armonía de la religión y el deseo de extender la vida, se detendrá en el Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts y predicará su futurista ideología en la Church of Perpetual Life, un templo transhumanista en Florida.

Como no podía ser de otra forma, el trayecto concluirá en Washington D.C., donde Istvan pretende hacer entrega de una Carta de Derechos de los Cíborgs en el mismísimo Congreso para pedir que se promueva la investigación en ciencia destinada a mejorar la especie.

"Ahora mismo, todos son religiosos todavía en América, planean morir e ir al cielo", señala Istvan. Por eso cree que "desafortunadamente" muchos estadounidenses todavía se muestran neutrales o incluso se oponen a detener la muerte biológica, y tratará de hacerlos cambiar de opinión con campañas mediáticas como este autobús de la inmortalidad.

Según nos cuenta este "hombre con la misión de acabar con la muerte", algunas televisiones ya se han comprometido a retransmitir su particular viaje y los primeros voluntarios ya se están sumando a su causa. Por el momento, no tiene una lista detallada de los activistas y personalidades que le acompañarán, pero nos cuenta que su esposa e hijas, la científicatranshumanista Maria Konovalenko o el bloguero y escritor Jamie Bartlett se subirán a este vehículo lleno de sorpresas.

"Muchos estudiantes universitarios se han convertido en voluntarios del Partido Transhumanista", detalla Istvan. A su juicio, los jóvenes de entre 16 y 30 años son el principal grupo de población preocupado por detener la muerte a tiempo, pero espera que muchos otros ciudadanos se sumen a la iniciativa y participen en los actos. "¡Pienso que querrán unirse simplemente porque es extraño y divertido!", asegura.

Si la campaña de crowdfunding no tiene el éxito que espera, este aventurero comprará el vehículo con el dinero de su propio bolsillo, aunque eso sí, la gira será más modesta de lo que en principio se planea. De todos modos, Istvan no pretende que su campaña se quede en Estados Unidos. Tras las elecciones, afirma que le encantaría viajar con su autobús de la inmortalidad por todo el mundo, primero a Europa y después a Asia.

Así que el día en que te encuentres un enorme ataúd circulando por tu calle, no te pellizques preguntándote si estás en tu barrio o en el otro. Se trata tan solo de un reclamo para que reflexiones sobre la necesidad de retrasar la muerte, la (por el momento) gran tragedia de la especie humana.

http://www.elconfidencial.com/tecno...ista-en-la-carrera-por-la-casa-blanca_950180/

Zoltan Istvan, el primer transhumanista en la carrera por la Casa Blanca

Zoltan Istvan aspira a convertirse en el primer presidente transhumanista de EEUU. Pretende recorrer el país concienciando sobre la necesidad de combatir la muerte mediante la ciencia y la tecnología

Un ataúd de 12 metros de largo, adornado con una tradicional corona floral, recorrerá los Estados Unidos sobre ruedas. Por fortuna, el féretro no albergará el cadáver de ningún adinerado excéntrico con deseos de innovar en el negocio de las funerarias aprovechando su último desplazamiento. La caja mortuoria se pondrá en marcha en septiembre con un propósito bien distinto: promocionar las ventajas de invertir en ciencia y tecnología para alcanzar la vida eterna.

El viaje contra el envejecimiento y la muerte que emprenderá este siniestro autobús es un proyecto del filósofo, escritor, exreportero del National Geographic y líder del Partido Transhumanista de Estados Unidos Zoltan Istvan. "Un ataúd era un poderoso y excelente símbolo del mayor miedo de mucha gente: tener que morir. Y el principal objetivo de los transhumanistas es superar la muerte gracias a la ciencia, así que un ataúd era un buen emblema", explica a Teknautas.

Hace unos meses, Istvan comenzó una campaña para presentarse comocandidato presidencial a la Casa Blanca en las elecciones de 2016, y ahora ha decidido emprender este road trip de la inmortalidad para reclamar de una forma original un debate sobre el derecho de los ciudadanos a retrasar su propia defunción.

Transhumanistas y robots, unidos por la vida eterna

Este filósofo reconvertido en político quiere conseguir financiación para comprar el autobús que se convertirá en féretro, así que ha lanzado una campaña en Indiegogo en busca de activistas y voluntarios que quieran apoyar su causa o incluso acompañarle en su viaje. Sus mecenas recibirán su eterna gratitud, un ebook con todos los detalles de la aventura o su novela The Transhumanist Wager (La Apuesta Transhumanista), entre otros obsequios.

En el momento de escribir estas líneas, Istvan ha logrado recaudar más de la mitad de los 25.000 dólares (casi 23.000 euros) que necesitaba para que el vehículo esté perfectamente equipado. Pese a su aspecto funerario, dispondrá de la más puntera tecnología en su interior.

Drones, un robot interactivo, equipos de realidad virtual, cámaras para grabar la experiencia y retransmitirla en directo o un laboratorio de biohacking para que los fans de experimentar con su cuerpo se entretengan serán algunos de los atractivos que viajarán a bordo de este autobús de la inmortalidad.

Istvan nos cuenta que los activistas contarán con microchips RFID listos para implantar en su cuerpo, además del instrumental necesario para colocarse imanes bajo los dedos y presumir de la capacidad de atraer objetos metálicos.

"El autobús atraerá a multitud de personas, pero debemos usar nuestras razones para convencer a la gente", señala Istvan. Ahora bien, ¿no es el periplo de este féretro un ejemplo de publicidad engañosa? ¿Podrá Istvan cumplir su ambiciosa promesa política de alargar nuestra vida si llega a presidente de los Estados Unidos?

Según este transhumanista, habrá tres posibilidades para superar la muerte: ralentizar la decadencia humana (los científicos ya han logrado revertir elenvejecimiento de los ratones), dejar que nuestra conciencia se traslade a una máquina o reemplazar aquellas partes de nuestro cuerpo que se vayan quedando inservibles por otros miembros y órganos artificiales, comocorazones robóticos. "Estamos seguros de que la inmortalidad será alcanzable en el futuro", afirma Istvan.

Una Carta de Derechos de los Cíborgs rumbo al Capitolio

Si todavía dudas entre recorrer la ruta 66 por tu cuenta o viajar por Estados Unidos rodeado de transhumanistas durante cuatro meses, has de saber que las paradas de este trayecto para combatir nuestra defunción son cuanto menos curiosas. La aventura comenzará en la costa oeste con el fin de celebrar un evento en cada estado. Istvan quiere organizar un acto en elcampus de Microsoft en Redmond, cerca de Seattle, charlas sobre la longevidad en Phoenix y un trayecto por las cercanías del río Mississippi para denunciar la contaminación de la naturaleza.

La excursión también transitará por el llamado cinturón bíblico de Estados Unidos, al sur del país, para reflexionar sobre la necesaria coexistencia en armonía de la religión y el deseo de extender la vida, se detendrá en el Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts y predicará su futurista ideología en la Church of Perpetual Life, un templo transhumanista en Florida.

Como no podía ser de otra forma, el trayecto concluirá en Washington D.C., donde Istvan pretende hacer entrega de una Carta de Derechos de los Cíborgs en el mismísimo Congreso para pedir que se promueva la investigación en ciencia destinada a mejorar la especie.

"Ahora mismo, todos son religiosos todavía en América, planean morir e ir al cielo", señala Istvan. Por eso cree que "desafortunadamente" muchos estadounidenses todavía se muestran neutrales o incluso se oponen a detener la muerte biológica, y tratará de hacerlos cambiar de opinión con campañas mediáticas como este autobús de la inmortalidad.

Según nos cuenta este "hombre con la misión de acabar con la muerte", algunas televisiones ya se han comprometido a retransmitir su particular viaje y los primeros voluntarios ya se están sumando a su causa. Por el momento, no tiene una lista detallada de los activistas y personalidades que le acompañarán, pero nos cuenta que su esposa e hijas, la científicatranshumanista Maria Konovalenko o el bloguero y escritor Jamie Bartlett se subirán a este vehículo lleno de sorpresas.

"Muchos estudiantes universitarios se han convertido en voluntarios del Partido Transhumanista", detalla Istvan. A su juicio, los jóvenes de entre 16 y 30 años son el principal grupo de población preocupado por detener la muerte a tiempo, pero espera que muchos otros ciudadanos se sumen a la iniciativa y participen en los actos. "¡Pienso que querrán unirse simplemente porque es extraño y divertido!", asegura.

Si la campaña de crowdfunding no tiene el éxito que espera, este aventurero comprará el vehículo con el dinero de su propio bolsillo, aunque eso sí, la gira será más modesta de lo que en principio se planea. De todos modos, Istvan no pretende que su campaña se quede en Estados Unidos. Tras las elecciones, afirma que le encantaría viajar con su autobús de la inmortalidad por todo el mundo, primero a Europa y después a Asia.

Así que el día en que te encuentres un enorme ataúd circulando por tu calle, no te pellizques preguntándote si estás en tu barrio o en el otro. Se trata tan solo de un reclamo para que reflexiones sobre la necesidad de retrasar la muerte, la (por el momento) gran tragedia de la especie humana.

http://www.elconfidencial.com/tecno...ista-en-la-carrera-por-la-casa-blanca_950180/

Pereirano

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 9.218

- Reacciones

- 3.459

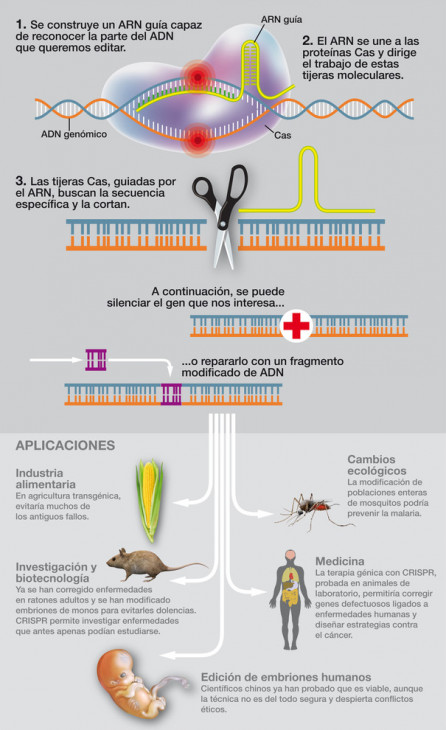

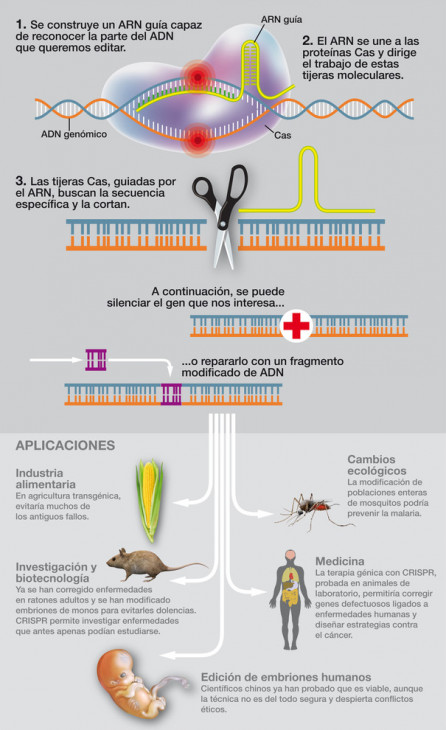

No se si habeis oido hablar de la tecnica CRISP/Cas9.Los cientificos han descubierto que las bacterias poseen una herramienta que les permite modificar su propio genoma y se esta aprendiendo a reprogramarla para que haga la misma tarea en cualquier otro organismo incluyendo los seres humanos.La cosa marcha viento en popa por lo que en no demasiado tiempo es muy probable que podamos editar nuestro genoma con una sencillez y precision sin precedentes.

Ya se conocen varios genes que elevan muy sustancialmente la longevidad en ratones y que teoricamente deberian funcionar de manera similar en los seres humanos.Esperemos que las investigaciones avancen lo mas rapido posible para que podamos pronto disfrutar de una mayor longevidad.

Las herramientas CRISPR: un regalo inesperado de las bacterias que ha revolucionado la biotecnología animal

¿Qué es la tecnología CRISPR/Cas9 y cómo nos cambiará la vida?

Ya se conocen varios genes que elevan muy sustancialmente la longevidad en ratones y que teoricamente deberian funcionar de manera similar en los seres humanos.Esperemos que las investigaciones avancen lo mas rapido posible para que podamos pronto disfrutar de una mayor longevidad.

LAS HERRAMIENTAS CRISPR: UN REGALO INESPERADO DE LAS BACTERIAS QUE HA REVOLUCIONADO LA BIOTECNOLOGÍA ANIMAL

Ejemplo de utilización de la tecnología CRISPR-Cas9 en ratones, para investigar la función de secuencias de ADN no codificantes del gen de la tirosinasa, implicada en la síntesis de melanina. El ratón editado mediante CRISPR-Cas9 (izquierda) muestra alteraciones en la pigmentación que no presenta el ratón silvestre, de referencia (a la derecha). Estos resultados se describen en el artículo científico Seruggia et al. 2015 Nucleic Acids Research, May 26;43(10):4855-67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv375 (Fotografía: Davide Seruggia)

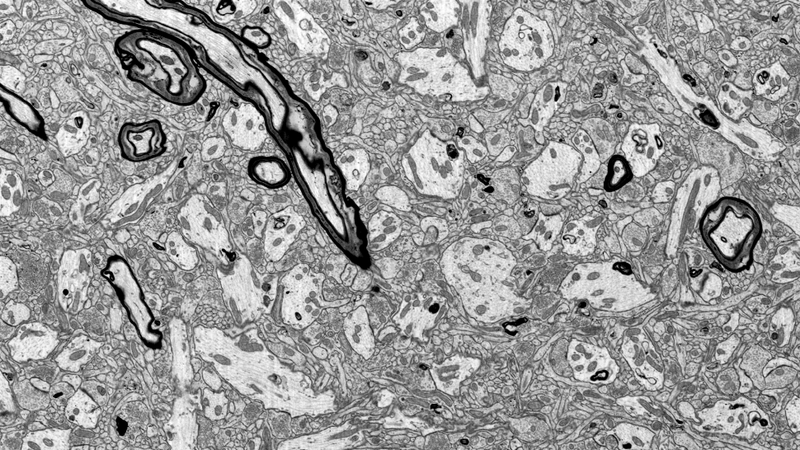

Hace poco más de dos años apareció un artículo científico publicado en la revista Cell que nos dejó boquiabiertos a todos quienes nos dedicamos a la biotecnología animal. En ese estudio se describía, por vez primera en ratones, una nueva forma de generar animales modificados genéticamente, mucho más rápida, precisa, eficaz, versátil y asequible. La generación de ratones transgénicos, mutantes o alterados genéticamente, por ejemplo, con fines biomédicos, con el objetivo de obtener modelos animales para el estudio de enfermedades humanas, era algo que sabíamos hacer desde la década de los años 80, del siglo pasado. Durante estos más de 30 años la tecnología que usábamos había cambiado naturalmente en algunos detalles, pero en lo substancial había evolucionado relativamente poco. La estrategia que diseñaron los investigadores Martin Evans, Mario Capecchi y Oliver Smithies para generar ratones mutantes específicos de un determinado gen, usando las células troncales embrionarias, y que les condujo a recibir el Premio Nobel de Fisiología o Medicina en 2007, seguía siendo el método de referencia en nuestros laboratorios en 2013, cuando apareció el mencionado artículo que ha desatado una verdadera revolución en la biotecnología animal.

Casi nadie podía sospechar que unas secuencias de ADN repetidas, descubiertas en bacterias en 1987 y en arqueas en 1993, y posteriormente interpretadas como parte de uno de los sistemas inmunes propios de las bacterias (que usan para defenderse de los virus que les atacan), se convertirían en una de las herramientas más sorprendentes que ha producido la biotecnología para modificar, a voluntad, y con una facilidad pasmosa, el genoma de cualquier organismo. Sin embargo, las investigadoras Emmanuelle Charpentier y Jennifer Doudna, tras años de investigación básica en microbiología y biología estructural, sí se dieron cuenta que este sistema de defensa de las bacterias, que se conocíacomo CRISPR desde 2002, podía convertirse fácilmente en una herramienta para la modificación dirigida del material genético de otros seres vivos. Tras diversos estudios realizados de forma independiente publicaron sus resultados conjuntamente en un artículo científico en la revista Science en agosto de 2012, que realmente fue la chispa que encendió la explosión posterior, encabezada por el artículo publicado en Cell en mayo de 2013. La magnitud de la revolución iniciada por estas dos investigadoras puede apreciarse por los premios y distinciones de prestigio que están recibiendo constantemente, entre los que destacan el Premio Princesa de Asturias de Investigación Científica y Técnica 2015, o el premio de la Sociedad Internacional de Tecnologías Transgénicas (ISTT), entre muchos otros. Y sus nombres suenan cada vez con más intensidad para el mayor de los galardones científicos.

¿Qué tiene de sorprendente el sistema CRISPR-Cas9? Su simplicidad y su extraordinaria eficacia. Este es un sistema de defensa optimizado durante miles de millones de años por las bacterias para lograr zafarse de los ataques de virus que les acechan constantemente en el medio ambiente. En esencia consta de dos elementos: una pequeña molécula de ARN (la parte CRISPR), que contiene una secuencia complementaria con la secuencia diana contra la que se dirige, en el ADN; y una endonucleasa (denominada Cas9), una proteína con actividad enzimática que es capaz de cortar el ADN y hacerlo solamente donde le indique la pequeña molécula de ARN mencionada. Al cortar la doble cadena de ADN de cualquier organismo en una posición determinada, una de las agresiones más peligrosas que puede recibir un genoma, pues representa la pérdida de la continuidad de la molécula de ADN, se pone en marcha un mecanismo ancestral, también existente en bacterias, que persigue reparar este corte cuanto antes. Para ello diversas enzimas, existentes en todas nuestras células, se encargan de empezar a digerir y reconstruir segmentos de ADN colindantes al corte, con objeto de localizar o generar alguna complementariedad que permita enganchar los dos extremos y restaurar la continuidad de la molécula de ADN. Durante este proceso se cometen errores y el sellado suele ir acompañado de la inserción o eliminación de algunos nucleótidos, las letras A, T, G, C que constituyen los genomas. Por lo tanto el resultado final es que allí donde se había producido un corte, al repararse éste, aparece una alteración genética, una mutación. Por lo tanto, mediante estas herramientas CRISPR-Cas9, dirigiendo un corte de ADN a una secuencia genética determinada, a un gen específico, se consigue generar una mutación específicamente en ese gen.

Las sorpresas no acaban ahí. Si, además, le damos un tercer elemento al sistema CRISPR-Cas9, una molécula de ADN que tenga secuencias complementarias alrededor de la zona donde se producirá el corte, e incorporamos en esta secuencia determinados cambios específicos, que no estuvieran presentes en el genoma original, el sistema tenderá a utilizar esta molécula de ADN como molde para restaurar el corte y, al hacerlo, cambiará el genoma. Lo habremos editado. Como si de un procesador de textos se tratara el sistema CRISPR-Cas9 y la molécula de ADN consiguen localizar un error y corregirlo en un gen, o, viceversa, instaurar un error donde antes no lo había, reproduciendo así en un modelo animal experimental aquella mutación detectada en un paciente afectado por una enfermedad de la cual se desconoce su efecto, sus consecuencias. El sueño de cualquier genetista, de cualquier biotecnólogo animal. No solamente somos capaces de modificar el genoma de nuestros modelos animales sino que podemos reproducir las mismas mutaciones que observamos en los pacientes, para estudiar cuáles son sus efectos y entender mejor la enfermedad, algo que antes ya era posible pero técnicamente difícil de abordar, y muy costoso, en tiempo, dinero y número de animales, y con metodologías que solamente estaban al alcance de los grandes centros de investigación en biomedicina.

¿Cuáles son los beneficios de generar animales mutantes con las herramientas CRISPR-Cas9? Es muy fácil de entender. Para generar un ratón mutante con la tecnología clásica de referencia se tardaba entre 8 y 12 meses de trabajo intenso en laboratorios muy especializados y expertos en las técnicas de modificación genética. Para generar un ratón mutante con las herramientas CRISPR-Cas9 se tarda de 1 a 2 meses en cualquier laboratorio mínimamente familiarizado con las técnicas básicas de biología molecular. Además, la generación de varios mutantes, posible antaño, alargaba mucho más el proceso, mientras que con las herramientas CRISPR-Cas9 pueden generarse, con idéntica facilidad, de forma simultánea, y en el mismo tiempo, mutaciones múltiples, que afecten a muchos genes. Simplemente hay que mantener la endonucleasa Cas9 y multiplicar oportunamente el número de pequeñas moléculas de ARN, una por cada gen que deseemos alterar. Y dejar que el sistema actúe. La proteína Cas9, cual tijera, cortará diligentemente en todas y cada una de las posiciones que le hayamos indicado, sean una o varias, le dará lo mismo, y lo hará sin rechistar.

¿Sorprendente? Sí. Y también una realidad. Una realidad que se ha extendido rapidísimamente por los centros de investigación biomédica de todo el mundo, en parte gracias a entidades como addgene tremendamente eficaces distribuyendo los elementos básicos para que cualquier laboratorio de cualquier parte del mundo pueda empezar a usar estas herramientas CRISPR-Cas9. ¡Y se trata de una técnica muy agradecida, robusta, que funciona! No hay nada como importar herramientas de las bacterias para que el éxito esté garantizado. Contamos con la ventaja de que ellas ya han mejorado, pulido cualquier sistema durante los miles de millones de años que llevan viviendo en la Tierra. Siempre que los animales (o las plantas) hemos tenido algún problema o reto genético que solucionar las bacterias han acudido en nuestra ayuda. Son una fuente inagotable de herramientas, de nuevas estrategias para la modificación genética, para el estudio de nuestros genomas.

¿Tiene alguna limitación este sistema? En Biología, en Biotecnología no existen los métodos o estrategias perfectas. La especificidad del corte de la proteína Cas9 vendrá determinada por la secuencia de ARN que dirija el corte a un sitio determinado del genoma y por la permisividad de la endonucleasa si se contenta con emparejamientos incompletos, en secuencias parecidas pero no idénticas. Debido a que nuestros genomas, sean de ratones o humanos, contienen muchas secuencias repetitivas, parecidas, si seleccionamos como secuencia diana una que esté presente muchas veces en un genoma provocaremos lo obvio, que se pierda la especificidad del corte y acaben alterándose muchos más genes de los inicialmente previstos. Por ello se han desarrollado recursos bioinformáticos que ayudan al investigador en su tarea de seleccionar qué secuencias de ADN pueden y deben usarse como dianas, con garantías de que estén representadas muy pocas veces en el genoma, idealmente únicas, y que permitan asegurar, con una determinada probabilidad, que solamente el gen diana, y no otros parecidos, se verá alterado. El temor inicial a una cierta promiscuidad del sistema cada vez se está despejando, al constatarse que las herramientas CRISPR-Cas9 son mucho más precisas y específicas de lo que imaginábamos.

¿Pueden aplicarse las herramientas CRISPR-Cas9 para modificar el genoma humano? En principio no hay nada que distinga a un embrión humano de un embrión de ratón para que sus correspondientes genomas puedan ser editados con estas nuevas herramientas. De hecho, en países en los que estos experimentos son posibles, como China, se acaban de publicar los primeros intentos de modificar el genoma humano realizados sobre embriones humanos no viables derivados de clínicas de infertilidad. Y los investigadores chinos han constatado lo obvio, lo mismo que otros investigadores habíamos visto en ratones y otras especies animales, que la técnica todavía no es lo suficiente segura ni fiable para su traslado desde los modelos experimentales a la clínica, para garantizar que las alteraciones genéticas precisas solamente ocurran en los genes previstos y de la forma esperada. Un nuevo ejemplo de por qué debemos seguir investigando con la ayuda de modelos animales, antes de saltar a los seres humanos.

Es evidente que la posibilidad real de modificar el genoma humano abre debates en nuestra sociedad más allá de la ciencia. Son muchos los posicionamientos y escritos que han aparecido, a favor y en contra de este posible uso, con todos sus matices. En mi opinión, los investigadores en biomedicina y biotecnología debemos seguir avanzando y aportando a la sociedad nuestro conocimiento, el resultado de nuestras investigaciones, de estrategias terapéuticas cada vez mejores y más eficaces para su eventual uso en humanos, para el tratamiento y la prevención de enfermedades. Y será después la sociedad, a través de sus representantes, con los datos e información adecuada, quien decidirá cuando está preparada para aceptar y trasladar estos avances científicos a las personas. La fecundación in vitro cuando se implantó en las clínicas de infertilidad humanas en los años 70 provocó un gran debate y rechazo en determinados sectores de la sociedad. Sin embargo hoy en día hay millones de niños y niñas nacidos gracias a esta técnica, ya rutinaria en muchos hospitales, y el médico que la desarrolló, Robert G. Edwards, recibió el Premio Nobel de Fisiología o Medicina en el año 2010.

Nuestro laboratorio, debido a un cúmulo de circunstancias favorables, fue de los primeros que empezó a utilizar con éxito esta nueva técnica de las herramientas CRISPR-Cas9 en ratones en nuestro país, ya desde sus inicios, en el año 2013. Hemos compartido el éxito con nuestros colegas, y enseñado a utilizar estas herramientas a muchos otros laboratorios, a través de estancias, colaboraciones, cursos y publicaciones y también a través de páginas web informativas abiertas a cualquier investigador interesado.

Para terminar, una reflexión y una perspectiva histórica.

Una reflexión: Las herramientas CRISPR-Cas9 son un ejemplo extraordinario de cómo una investigación básica (el sistema inmune de las bacterias), aparentemente alejada de las investigaciones aplicadas finalistas, puede llegar a convertirse en una aplicación tremendamente útil (la modificación de cualquier genoma a voluntad) en biología, biotecnología y biomedicina. Ilustra magníficamente como cualquier sistema público o privado de investigación debe continuar invirtiendo en ciencia básica, no finalista, pues hay que sembrar en muchas direcciones, hay que ir descubriendo lo desconocido, para poder recolectar años después allí donde se hayan dado las condiciones para que la semilla germine y florezca, allí donde haya saltado la chispa!.

Una perspectiva histórica: Muchos investigadores todavía desconocen que en España contamos con uno de los primeros microbiólogos que descubrieron las CRISPR en arqueas en 1993. Francisco Juan Martínez Mojica (Universidad de Alicante) realizó su tesis doctoral con estas secuencias repetidas y ha seguido estudiándolas sistemáticamente durante toda su carrera científica, aislándolas y describiéndolas en muchas especies de arqueas y bacterias. Tanto es así que fue quien acuñó el término CRISPR (acrónimo del inglés Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) que es el que ahora utiliza toda la comunidad científica internacional, como le reconocieron unos microbiólogos holandeses en 2002, y fue también quien primero sugirió que estas secuencias podían estar relacionadas con la inmunidad de las bacterias a la infección por determinados virus, en 2005, dos años antes que se descubriera y publicara que, efectivamente, las CRISPRs son una parte de un sistema inmune de las bacterias. Francisco J. M. Mojica intuyó que estos sistemas CRISPR-Cas podrían tener aplicaciones en biología y en biomedicina, principalmente desde el punto de vista de poder estudiar y modificar la inmunidad de las bacterias, para poder combatirlas con mayor eficacia. Sin embargo no imaginó que fueran a ser tan útiles en animales para la edición de genomas. Emmanuelle Charpentier y Jennifer Doudna sí se percataron del potencial que albergaban estas herramientas CRISPR-Cas9, y por ello están recibiendo los honores, con todo merecimiento. Sin embargo ellas no olvidan que no hubieran podido avanzar en sus investigaciones sin el trabajo pionero y sistemático de microbiólogos básicos como Francisco J. M. Mojica y por eso le reconocieron el crédito que merecía citando los experimentos del investigador alicantino de forma relevante en su ya famosa revisión publicada en Science en noviembre de 2014. El merecido aunque tardío reconocimiento le llegó a Francis J.M. Mojica desde el extranjero.

Lluís Montoliu @LluisMontoliu

Investigador Científico del CSIC

Centro Nacional de Biotecnología

Las herramientas CRISPR: un regalo inesperado de las bacterias que ha revolucionado la biotecnología animal

¿Qué es la tecnología CRISPR/Cas9 y cómo nos cambiará la vida?

Posted by Alberto Morán On marzo 09, 2015 0 Comment

La tecnología CRISPR/Cas9 es una herramienta molecular utilizada para “editar” o “corregir” el genoma de cualquier célula. Eso incluye, claro está, a las células humanas. Sería algo así como unas tijeras moleculares que son capaces de cortar cualquier molécula de ADN haciéndolo además de una manera muy precisa y totalmente controlada. Esa capacidad de cortar el ADN es lo que permite modificar su secuencia, eliminando o insertando nuevo ADN.

Las siglas CRISPR/Cas9 provienen de Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, en español “Repeticiones Palindrómicas Cortas Agrupadas y Regularmente interespaciadas.” La segunda es el nombre de una serie de proteínas, principalmente unas nucleasas, que las llamaron así por CRISPR associated system (es decir: “sistema asociado a CRISPR”).

¿Cómo surgió?

Todo comenzó en 1987 cuando se publicó un artículo en el cual se describía cómo algunas bacterias (Streptococcus pyogenes) se defendían de las infecciones víricas. Estas bacterias tienen unas enzimas que son capaces de distinguir entre el material genético de la bacteria y el del virus y, una vez hecha la distinción, destruyen al material genético del virus.

Streptococcus pyogenes

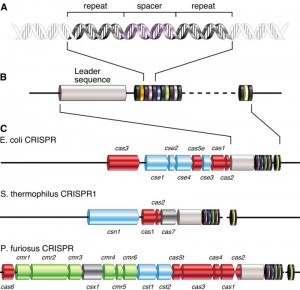

Sin embargo, las bases de este mecanismo no se conocieron hasta más adelante, cuando se mapearon los genomas de algunas bacterias y otros microorganismos. Se encontró que una zona determinada del genoma de muchos microorganismos, sobre todo arqueas, estaba llena de repeticiones palindrómicas (que se leen igual al derecho y al revés) sin ninguna función aparente. Estas repeticiones estaban separadas entre sí mediante unas secuencias denominadas “espaciadores” que se parecían a otras de virus y plásmidos. Justo delante de esas repeticiones y “espaciadores” hay una secuencia llamada “líder”. Estas secuencias son las que se llamaron CRISPR (“Repeticiones Palindrómicas Cortas Agrupadas y Regularmente interespaciadas”). Muy cerca de este agrupamiento se podían encontrar unos genes que codificaban para un tipo de nucleasas: los genes cas.

Las secuencias repetidas del CRISPR. Tomado de: Karginov FV y Hannon GJ. Mol Cell 2010

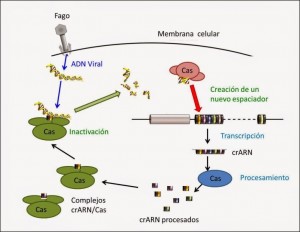

Cuando un virus entra dentro de la bacteria toma el control de la maquinaria celular y para ello interacciona con distintos componentes celulares. Pero las bacterias que tienen este sistema de defensa tienen un complejo formado por una proteína Cas unida al ARN producido a partir de las secuencias CRISPR. Entonces el material génico del virus puede interaccionar con este complejo. Si ocurre eso, el material genético viral es inactivado y posteriormente degradado. Pero el sistema va más allá. Las proteínas Cas son capaces de coger una pequeña parte del ADN viral, modificarlo e integrarlo dentro del conjunto de secuencias CRISPR. De esa forma, si esa bacteria (o su descendencia) se encuentra con ese mismo virus, ahora inactivará de forma mucho más eficiente al material genético viral. Es, por lo tanto, un verdadero sistema inmune de bacterias.

Proceso por el que el sistema CRISPR/Cas9 inactiva virus e integra parte de sus secuencias en el genoma de la bacteria.

Durante los años subsiguientes se continuó la investigación sobre este sistema, pero no fue hasta el año 2012 en el que se dio el paso clave para convertir este descubrimiento, esta observación biológica en una herramienta molecular útil en el laboratorio. En agosto de este año un equipo de investigadores dirigido por las doctoras Emmanuelle Charpentier en la Universidad de Umeå y Jennifer Doudna, en la Universidad de California en Berkeley, publicó un artículo en la revistaScience el que se demostraba cómo convertir esa maquinaria natural en una herramienta de edición “programable”, que servía para cortar cualquier cadena de ADN in vitro. Es decir, lograban programar el sistema para que se dirigiera a una posición específica de un ADN cualquiera (no solo vírico) y lo cortaran.

Jennifer Doudna y Emmanuelle Charpentier

La manera en que lo lograron es demasiado compleja para lo que pretende este blog. Baste simplemente decir que se utilizan unos ARNs que dirigen el sistema hacia el ADN que hay que cortar.

¿Cómo se edita el ADN con esta tecnología?

Todo comienza con el diseño de una molécula de ARN (CRISPR o ARN guía) que luego va a ser insertada en una célula. Una vez dentro reconoce el sitio exacto del genoma donde la enzima Cas9 deberá cortar.

El proceso de editar un genoma con CRISPR/Cas9 incluye dos etapas. En la primer atapa el ARN guía se asocia con la enzima Cas9. Este ARN guía es específico de una secuencia concreta del ADN, de tal manera que por las reglas decomplementariedad de nucleótidos se hibridará en esa secuencia (la que nos interesa editar o corregir). Entonces actúa Cas9, que es una enzima endonucleasa (es decir, una proteína que es capaz de romper un enlace en la cadena de los ácidos nucléicos), cortando el ADN. Básicamente podemos decir que el ARN guía actúa de perro lazarillo llevando a Cas9, el ejecutor, al sitio donde ha de realizar su función.

En la segunda etapa se activan al menos dos mecanismos naturales de reparación del ADN cortado. El primero llamado indel(inserción-deleción) hace que, después del sitio de corte (la secuencia específica del ADN donde se unió el ARN guía), bien aparezca un hueco en la cadena, bien se inserte un trocito más de cadena. Esto conlleva a la perdida de la función original del segmento de ADN cortado.

Un segundo mecanismo permite la incorporación de una secuencia concreta exactamente en el sitio original de corte. Para esto, lógicamente, hemos de darle a la célula la secuencia que queremos que se integre en el ADN.

Aquí tenéis un vídeo explicativo del sistema:

Problemas que puede tener

En principio tiene dos pegas técnicas que han de ser corregidas (ya se está en ello). La primera viene derivada del hecho de que la especificidad del ARN guía no es total. Es decir, este ARN, puede hibridar, juntarse con más de un sitio en el genoma, lo que llevaría a que la enzima Cas9 cortara en un sitio que no nos interese. Hay que recordar que el genoma está compuesto por sucesiones de cuatro “letras”, A, T, G, y C, y la posibilidad de que se repita determinada secuencia es alta, sobre todo si la secuencia no es muy larga (es probable que, por ejemplo, la secuencia AAATGGCAATC esté en más de un gen. La probabilidad de repetición disminuye si aumento la longitud de la “palabra”). El segundo punto débil de la técnica se debe a que Cas9 pueda cortar sin que esté presente el ARN guía. Esto se soluciona con enzimas más precisas.

¿Para qué vale?

De manera molecular podemos decir que esta herramienta se podrá utilizar para regular la expresión génica, etiquetar sitios específicos del genoma en células vivas, identificar y modificar funciones de genes y corregir genes defectuosos. También se está ya utilizando para crear modelos de animales para estudiar enfermedades complejas como la esquizofrenia, para las que antes no existían modelos animales.

Mingling y Lingling, dos gemelas de macaco cuyo genoma fue editado por medio de Crispr/Cas9

¿Cómo nos va a cambiar la vida?

Las posibilidades son casi inimaginables. Con la tecnología CRISPR/Cas9 se inaugura una nueva era de ingeniería genética en la que se puede editar, corregir, alterar, el genoma de cualquier célula de una manera fácil, rápida, barata y, sobre todo, altamente precisa. Cambiar el genoma significa cambiar lo esencial de un ser, recordadlo.

En un futuro relativamente cercano servirá para curar enfermedades cuya causa genética se conozca y que hasta ahora eran incurables. Es lo que seguramente muchas veces habréis oído nombrar como terapia génica. Ya se está trabajando con esta tecnología en estas enfermedades como la Corea de Huntington, el Síndrome de Down o la anemia falciforme. Otra aplicación aparentemente futurista, pero no tan quimérica es la reprogramación de nuestras células para que corten el genoma del VIH.

Así, el MIT (Instituto Tecnológico de Massachussets) anunció ya en marzo de 2014 que había conseguido curar a un ratón adulto de una enfermedad hepática (tirosinemia de tipo I) de origen genético utilizando esta tecnología.

Y, sí, como muchos estáis pensando, esta técnica también vale para modificar los genomas de embriones humanos. Sobre las implicaciones éticas y sociales habría que escribir muchos libros, pero no es nuestro objeto aquí.

Además de estas implicaciones sanitarias, también se puede utilizar para mejorar los alimentos transgénicos (desarrollar nuevas variedades de plantas y animales con características genéticas concretas), modificar bacterias y otros microorganismos de uso industrial y alimentario.

Guerra de patentes

La ciencia también tiene una parte “fea”. Y en esta ocasión, como casi siempre, viene derivada de los intereses económicos (obvios) que tiene la tecnología CRISPR/Cas9.

Poco después del famoso artículo de Doudna y Charpentier, en enero de 2013 los laboratorios de George Church en Harvard y Feng Zhang en el Broad Institute del MIT fueron los primeros en publicar artículos demostrando que CRISPR/Cas9 servía para células humanas. Doudna publicó lo propio de manera independiente apenas unas semanas más tarde.

En abril de 2014 Zhang y el Instituto Broad obtuvieron la primera de entre varias patentes generales que cubren el uso de CRISPR en eucariotas. Eso les otorgaba los derechos para usar CRISPR en ratones, cerdos, humanos… prácticamente en cualquier criatura que no fuera una bacteria.

La velocidad de obtención de la patente sorprendió a algunos. Y fue porque el Instituto Broad había pagado de una manera discreta para que la revisaran muy rápido, en menos de seis meses. Además el proceso se llevó a cabo de una manera casi “secreta”. Junto con la patente llegaron más de mil páginas de documentos. Doudna había presentado antes que la de Zhang, una solicitud de patente. Pero, según Zhang, la predicción de Doudna en su solicitud de que su descubrimiento funcionaría en humanos era una “mera conjetura” y que en cambio él fue el primero en demostrarlo en un acto de invención distinto y “sorprendente”. Para demostrar que fue “el primero en inventar” el uso de CRISPR-Cas en células humanas, Zhang presentó fotos de cuadernos de laboratorio que según él demuestran que tenía el sistema en marcha a principios de 2012, incluso antes de que Doudna y Charpentier publicaran sus resultados o solicitaran su propia patente. Esa cronología significaría que él descubrió el sistema CRISPR-Cas independientemente. En una entrevista, Zhang afirmó que había hecho los descubrimientos él solo. Al preguntársele qué había aprendido del artículo de Doudna y Charpentier, dijo “no mucho”.

Por otra parte, los abogados de Doudna y Charpentier no se van a quedar de brazos cruzados y se espera que monten un “procedimiento de interferencia” en Estados Unidos, que es un proceso legal en el que el ganador se lo lleva todo y en el que un inventor puede hacerse con la patente de otro.

En el juego de las patentes aparecen implicadas tres start-up para las que el control de esas patentes es clave. Entre esas empresas están Editas Medicine, Intellia Therapeutics, ambas de Cambridge, y CRISPR Therapeutics, una start-up de Basilea (Suiza) cofundada por Charpentier. Zhang cofundó Editas Medicine, que en diciembre de 2014 anunció que había comprado la licencia para el uso de su patente al Instituto Broad. Pero Editas no tiene el monopolio sobre CRISPR porque Doudna también fue cofundadora de la empresa. Y desde que salió la patente de Zhang, Doudna ha roto con la empresa, y su propiedad intelectual en forma de su propia patente pendiente de aprobación se ha vendido bajo licencia a Intellia. Para complicar aún más las cosas, Charpentier vendió sus derechos de la misma solicitud de patente a CRISPR Therapeutics.

Por otra parte, cada vez hay más voces que piden que, debido a la gran capacidad de curar enfermedades por parte de CRISPR-Cas9, la tecnología no quede protegida por patente y se deje como acceso público. La propia Charpentier asegura que la tecnología ha sido puesta libremente a disposición de la comunidad investigadora, por lo que no cree que la patente suponga ningún obstáculo al avance científico.

Veremos qué nos depara el futuro.

¿Qué es la tecnología CRISPR/Cas9 y cómo nos cambiará la vida?

Pereirano

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 9.218

- Reacciones

- 3.459

Scientists discover new system for human genome editing

September 25, 2015

CRISPR systems help bacteria defend against viral attack (shown here). These systems have been adapted for use as genome editing tools in human cells. Image by Ami Images/Science Photo Library

A team including the scientist who first harnessed the revolutionary CRISPR-Cas9 system for mammalian genome editing has now identified a different CRISPR system with the potential for even simpler and more precise genome engineering.

In a study published today in Cell, Feng Zhang and his colleagues at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard and the McGovern Institute for Brain Research at MIT, with co-authors Eugene Koonin at the National Institutes of Health, Aviv Regev of the Broad Institute and the MIT Department of Biology, and John van der Oost at Wageningen University, describe the unexpected biological features of this new system and demonstrate that it can be engineered to edit the genomes of human cells.

"This has dramatic potential to advance genetic engineering," said Eric Lander, Director of the Broad Institute and one of the principal leaders of the human genome project. "The paper not only reveals the function of a previously uncharacterized CRISPR system, but also shows that Cpf1 can be harnessed for human genome editing and has remarkable and powerful features. The Cpf1 system represents a new generation of genome editing technology."

CRISPR sequences were first described in 1987 and their natural biological function was initially described in 2010 and 2011. The application of the CRISPR-Cas9 system for mammalian genome editing was first reported in 2013, by Zhang and separately by George Church at Harvard.

In the new study, Zhang and his collaborators searched through hundreds of CRISPR systems in different types of bacteria, searching for enzymes with useful properties that could be engineered for use in human cells. Two promising candidates were the Cpf1 enzymes from bacterial species Acidaminococcus and Lachnospiraceae, which Zhang and his colleagues then showed can target genomic loci in human cells.

"We were thrilled to discover completely different CRISPR enzymes that can be harnessed for advancing research and human health," Zhang said.

The newly described Cpf1 system differs in several important ways from the previously described Cas9, with significant implications for research and therapeutics, as well as for business and intellectual property:

"The unexpected properties of Cpf1 and more precise editing open the door to all sorts of applications, including in cancer research," said Levi Garraway, an institute member of the Broad Institute, and the inaugural director of the Joint Center for Cancer Precision Medicine at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women's Hospital, and the Broad Institute. Garraway was not involved in the research.

- First: In its natural form, the DNA-cutting enzyme Cas9 forms a complex with two small RNAs, both of which are required for the cutting activity. The Cpf1 system is simpler in that it requires only a single RNA. The Cpf1 enzyme is also smaller than the standard SpCas9, making it easier to deliver into cells and tissues.

- Second, and perhaps most significantly: Cpf1 cuts DNA in a different manner than Cas9. When the Cas9 complex cuts DNA, it cuts both strands at the same place, leaving 'blunt ends' that often undergo mutations as they are rejoined. With the Cpf1 complex the cuts in the two strands are offset, leaving short overhangs on the exposed ends. This is expected to help with precise insertion, allowing researchers to integrate a piece of DNA more efficiently and accurately.

- Third: Cpf1 cuts far away from the recognition site, meaning that even if the targeted gene becomes mutated at the cut site, it can likely still be re-cut, allowing multiple opportunities for correct editing to occur.

- Fourth: the Cpf1 system provides new flexibility in choosing target sites. Like Cas9, the Cpf1 complex must first attach to a short sequence known as a PAM, and targets must be chosen that are adjacent to naturally occurring PAM sequences. The Cpf1 complex recognizes very different PAM sequences from those of Cas9. This could be an advantage in targeting some genomes, such as in the malaria parasite as well as in humans.

Zhang, Broad Institute, and MIT plan to share the Cpf1 system widely. As with earlier Cas9 tools, these groups will make this technology freely available for academic research via the Zhang lab's page on the plasmid-sharing-website Addgene, through which the Zhang lab has already shared Cas9 reagents more than 23,000 times to researchers worldwide to accelerate research. The Zhang lab also offers free online tools and resources for researchers through its website, http://www.genome-engineering.org.

The Broad Institute and MIT plan to offer non-exclusive licenses to enable commercial tool and service providers to add this enzyme to their CRISPR pipeline and services, further ensuring availability of this new enzyme to empower research. These groups plan to offer licenses that best support rapid and safe development for appropriate and important therapeutic uses. "We are committed to making the CRISPR-Cpf1 technology widely accessible," Zhang said.

"Our goal is to develop tools that can accelerate research and eventually lead to new therapeutic applications. We see much more to come, even beyond Cpf1 and Cas9, with other enzymes that may be repurposed for further genome editing advances."

More information: Zetsche et al., Cpf1 Is a Single RNA-Guided Endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas System, Cell (2015), dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038

Provided by: Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard

http://m.phys.org/news/2015-09-scientists-human-genome.html

Pereirano

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 9.218

- Reacciones

- 3.459

Otra interesante conferencia:

Tecnologías Emergentes, Singularidad Tecnológica y la Visión Transhumanista por Giulio Prisco

http://www.ub.edu/ubtv/es/video/tec...gica-y-la-vision-transhumanista-giulio-prisco

Tecnologías Emergentes, Singularidad Tecnológica y la Visión Transhumanista por Giulio Prisco

http://www.ub.edu/ubtv/es/video/tec...gica-y-la-vision-transhumanista-giulio-prisco

Pereirano

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 9.218

- Reacciones

- 3.459

Experimental drug targeting Alzheimer's disease shows anti-aging effects in animal tests

Salk Institute researchers have found that an experimental drug candidate aimed at combating Alzheimer’s disease has a host of unexpected anti-aging effects in animals.

The Salk team expanded upon their previous development of a drug candidate, called J147, which takes a different tack by targeting Alzheimer’s major risk factor–old age. In the new work, the team showed that the drug candidate worked well in a mouse model of aging not typically used in Alzheimer’s research. When these mice were treated with J147, they had better memory and cognition, healthier blood vessels in the brain and other improved physiological features.

“Initially, the impetus was to test this drug in a novel animal model that was more similar to 99 percent of Alzheimer's cases,” says Antonio Currais, the lead author and a member of Professor David Schubert’s Cellular Neurobiology Laboratory at Salk. “We did not predict we’d see this sort of anti-aging effect, but J147 made old mice look like they were young, based upon a number of physiological parameters.”

Journal Aging -A comprehensive multiomics approach toward understanding the relationship between aging and dementia

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive brain disorder, recently ranked as the third leading cause of death in the United States and affecting more than five million Americans. It is also the most common cause of dementia in older adults, according to the National Institutes of Health. While most drugs developed in the past 20 years target the amyloid plaque deposits in the brain (which are a hallmark of the disease), few have proven effective in the clinic.

“While most drugs developed in the past 20 years target the amyloid plaque deposits in the brain (which are a hallmark of the disease), none have proven effective in the clinic,” says Schubert, senior author of the study.

Several years ago, Schubert and his colleagues began to approach the treatment of the disease from a new angle. Rather than target amyloid, the lab decided to zero in on the major risk factor for the disease–old age. Using cell-based screens against old age-associated brain toxicities, they synthesized J147.

Previously, the team found that J147 could prevent and even reverse memory loss and Alzheimer’s pathology in mice that have a version of the inherited form of Alzheimer's, the most commonly used mouse model. However, this form of the disease comprises only about 1 percent of Alzheimer's cases. For everyone else, old age is the primary risk factor, says Schubert. The team wanted to explore the effects of the drug candidate on a breed of mice that age rapidly and experience a version of dementia that more closely resembles the age-related human disorder.

In this latest work, the researchers used a comprehensive set of assays to measure the expression of all genes in the brain, as well as over 500 small molecules involved with metabolism in the brains and blood of three groups of the rapidly aging mice. The three groups of rapidly aging mice included one set that was young, one set that was old and one set that was old but fed J147 as they aged.

The old mice that received J147 performed better on memory and other tests for cognition and also displayed more robust motor movements. The mice treated with J147 also had fewer pathological signs of Alzheimer's in their brains. Importantly, because of the large amount of data collected on the three groups of mice, it was possible to demonstrate that many aspects of gene expression and metabolism in the old mice fed J147 were very similar to those of young animals. These included markers for increased energy metabolism, reduced brain inflammation and reduced levels of oxidized fatty acids in the brain.

Another notable effect was that J147 prevented the leakage of blood from the microvessels in the brains of old mice. “Damaged blood vessels are a common feature of aging in general, and in Alzheimer's, it is frequently much worse,” says Currais.

Currais and Schubert note that while these studies represent a new and exciting approach to Alzheimer’s drug discovery and animal testing in the context of aging, the only way to demonstrate the clinical relevance of the work is to move J147 into human clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease.

“If proven safe and effective for Alzheimer’s, the apparent anti-aging effect of J147 would be a welcome benefit,” adds Schubert. The team aims to begin human trials next year.

Abstract

Because age is the greatest risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (AD), phenotypic screens based upon old age‐associated brain toxicities were used to develop the potent neurotrophic drug J147. Since certain aspects of aging may be primary cause of AD, we hypothesized that J147 would be effective against AD‐associated pathology in rapidly aging SAMP8 mice and could be used to identify some of the molecular contributions of aging to AD. An inclusive and integrative multiomics approach was used to investigate protein and gene expression, metabolite levels, and cognition in old and young SAMP8 mice. J147 reduced cognitive deficits in old SAMP8 mice, while restoring multiple molecular markers associated with human AD, vascular pathology, impaired synaptic function, and inflammation to those approaching the young phenotype. The extensive assays used in this study identified a subset of molecular changes associated with aging that may be necessary for the development of AD.

SOURCES - Salk Institute, Journal Aging

Next Big Future: Experimental drug targeting Alzheimer's disease shows anti-aging effects in animal tests

Pereirano

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 9.218

- Reacciones

- 3.459

Geneticists Are Concerned Transhumanists Will Use CRISPR on Themselves

WRITTEN BY ALEX PEARLMAN

Geneticists developing powerful genome editing tools are worried that transhumanists will try to use them on themselves before they’re deemed safe and effective for use in humans, which could undermine the future of technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, that allow for specific, targeted DNA editing.

Many of the biggest names in the field are at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, where they are trying to reach a consensus on when, how, and for what purposes humans should edit their own DNA (or the DNA of an embryo).

CRISPR holds promise in the potential eradication of diseases like HIV, Huntington’s, and Alzheimer’s, and could be used to prevent children from being born mentally impaired. The scientific community seems to generally agree that using CRISPR to potentially prevent disease is ethically OK as long as the technology overall is deemed safe for use in humans. Things get sticky, however, when you consider that gene editing could theoretically be used down the line to create designer babies, to prevent premature aging, or to stimulate muscle growth, among myriad other applications.

Transhumanists, many of whom believe science can be used to ultimately conquer death, look at CRISPR as an important part of the toolkit we can use to transcend our natural bodies. Since as early as 2004, transhumanist groups have opposed the idea of bans on human genetic editing research. Zoltan Istvan, who is running for president as a Transhumanist candidate (and who writes an occasional column for Motherboard), says CRISPR holds great promise for the human race.

“Despite some people saying CRISPR technology could lead to dangerous outcomes for the human race, the positive possibilities far outweigh any dangers,” Istvan told me in an email. “With this type of gene editing tech we have a chance to wipe out hereditary diseases and conditions that plague humanity. And we could also modify the human being to be much stronger and functional than it is. CRISPR could be one of the most important scientific advancements of the 21st Century. We should embrace it.”

George Church says CRISPR will be ready for public use sooner than you'd think. Image: George Church

George Church, a researcher at Harvard University and one of the most outspoken proponents of CRISPR, says that, considering the lack of clear regulatory frameworks for its use, we must expect those interested in genetic augmentation to use the tool.

Church noted in a speech Tuesday that athletes and others interested in body augmentation have already taken advantage of just about every technology we’ve developed. Those in the transhumanist movement (many of whom are seeking immortality, or at the very least a long extension of natural human lifespans) see CRISPR as a potential tool they could use to augment themselves.

"We’re probably going to need new international oversight structures so that we don’t realize these dystopian Brave New World examples"

“I’m thinking of it as more of a slippery slope,” Church said. When it comes to people using CRISPR to augment themselves or their children, “some people say ‘I can’t imagine it happening’ And I say, ‘You have to imagine it happening.’”

Church and some others who work with CRISPR believe that it’s already safe enough for additional research in humans, but, in the only known test of the technology on human embryos, CRISPR was largely ineffective in editing the desired genes. Abreakthrough announced earlier this week enhances CRISPR’s accuracy and may be key to future human studies. As those eventual studies are conducted and as the technology becomes more consistent, Church believes somatic gene therapies, which target adult body cells (and could in theory be used by adults to alter themselves) will inevitably come next.

“Enhancement will creep in the door,” Church said. “The point is that [human enhancements] will come after very serious diseases and they will be spread by somatic gene therapies.”

Church and George Daley of Boston Children’s Hospital believe that we’d be naive to expect interested people to not edit themselves out of a sense of morality—or even because the science and policies around it are in their infancy.

Already, those interested in enhancement are gung-ho about experimenting on themselves. There are athletes who take stem cell injections to get over injury faster; Silicon Valley types who use nootropics and other “smart drugs” not approved by the Food and Drug Administration to potentially increase their brain function; and people who try things like transcranial direct current stimulation, which uses low electrical currents applied to the head to stimulate neuron function.

One of Daley's slides suggested that "enhancements" are on the table. Image: George Daley

Lance Armstrong admitted to injecting himself with erythropoietin, a hormone that stimulates the production of red blood cells, to help him win the Tour de France. Daley said that it’d be possible to use CRISPR to make your stem cells naturally create more of the hormone.

“Why depend on injecting yourself with erythropoietin if you wanted to win the Tour de France?,” Daley said. “Why not just modify your hematopoietic stem cells to produce more erythropoietin?”

Considering how we’ve used every other medical technology for the arguably less “ethical” use of human enhancement, why wouldn’t transhumanists try out CRISPR—if it becomes available—to literally change their (or their unborn children’s) DNA to make them stronger, faster, smarter, or less disease-prone?

“We’re probably going to need new international oversight structures so that we don’t realize these dystopian Brave New World examples,” Daley said at the summit.

Should such uses of CRISPR be outlawed? Are they unethical? It’s hard to say—but bioethicists and regulators are concerned that a mutation or unsafe gene could be put into the human germline, meaning that it would be passed from generation to generation.

“We also need to regulate the specific uses of the products because we’re all concerned about off-label use,” Barbara Evans, director of the Center for Bioethics and Law at the University of Houston, said Wednesday.

More conservative voices from the bioethics community are advocating for a full ban on the technology, regardless of how it’s used. But just because some people want to use the technology in ways that so-called “bioconservatives” may not like, Daley says it’d be wrong for regulators dismiss CRISPR’s human potential.

“There are some who are going to say, ‘No we shouldn’t go through that exercise at all—the technology has no real legitimate uses, therefore we don’t have to worry, we just ban it,’” Daley said. “But I think we want a more nuanced argument than that. And that is, I think, what we’re trying to figure out here.”

TOPICS: gene editing, International Summit on Human Gene Editing, CRISPR,CRISPR/Cas9, Futures, genetics, news, transhumanism, zoltan istvan

Geneticists Are Concerned Transhumanists Will Use CRISPR on Themselves

WRITTEN BY ALEX PEARLMAN

Geneticists developing powerful genome editing tools are worried that transhumanists will try to use them on themselves before they’re deemed safe and effective for use in humans, which could undermine the future of technologies, such as CRISPR/Cas9, that allow for specific, targeted DNA editing.

Many of the biggest names in the field are at the International Summit on Human Gene Editing, where they are trying to reach a consensus on when, how, and for what purposes humans should edit their own DNA (or the DNA of an embryo).

CRISPR holds promise in the potential eradication of diseases like HIV, Huntington’s, and Alzheimer’s, and could be used to prevent children from being born mentally impaired. The scientific community seems to generally agree that using CRISPR to potentially prevent disease is ethically OK as long as the technology overall is deemed safe for use in humans. Things get sticky, however, when you consider that gene editing could theoretically be used down the line to create designer babies, to prevent premature aging, or to stimulate muscle growth, among myriad other applications.

Transhumanists, many of whom believe science can be used to ultimately conquer death, look at CRISPR as an important part of the toolkit we can use to transcend our natural bodies. Since as early as 2004, transhumanist groups have opposed the idea of bans on human genetic editing research. Zoltan Istvan, who is running for president as a Transhumanist candidate (and who writes an occasional column for Motherboard), says CRISPR holds great promise for the human race.

“Despite some people saying CRISPR technology could lead to dangerous outcomes for the human race, the positive possibilities far outweigh any dangers,” Istvan told me in an email. “With this type of gene editing tech we have a chance to wipe out hereditary diseases and conditions that plague humanity. And we could also modify the human being to be much stronger and functional than it is. CRISPR could be one of the most important scientific advancements of the 21st Century. We should embrace it.”

George Church says CRISPR will be ready for public use sooner than you'd think. Image: George Church

George Church, a researcher at Harvard University and one of the most outspoken proponents of CRISPR, says that, considering the lack of clear regulatory frameworks for its use, we must expect those interested in genetic augmentation to use the tool.

Church noted in a speech Tuesday that athletes and others interested in body augmentation have already taken advantage of just about every technology we’ve developed. Those in the transhumanist movement (many of whom are seeking immortality, or at the very least a long extension of natural human lifespans) see CRISPR as a potential tool they could use to augment themselves.

"We’re probably going to need new international oversight structures so that we don’t realize these dystopian Brave New World examples"

“I’m thinking of it as more of a slippery slope,” Church said. When it comes to people using CRISPR to augment themselves or their children, “some people say ‘I can’t imagine it happening’ And I say, ‘You have to imagine it happening.’”

Church and some others who work with CRISPR believe that it’s already safe enough for additional research in humans, but, in the only known test of the technology on human embryos, CRISPR was largely ineffective in editing the desired genes. Abreakthrough announced earlier this week enhances CRISPR’s accuracy and may be key to future human studies. As those eventual studies are conducted and as the technology becomes more consistent, Church believes somatic gene therapies, which target adult body cells (and could in theory be used by adults to alter themselves) will inevitably come next.

“Enhancement will creep in the door,” Church said. “The point is that [human enhancements] will come after very serious diseases and they will be spread by somatic gene therapies.”

Church and George Daley of Boston Children’s Hospital believe that we’d be naive to expect interested people to not edit themselves out of a sense of morality—or even because the science and policies around it are in their infancy.

Already, those interested in enhancement are gung-ho about experimenting on themselves. There are athletes who take stem cell injections to get over injury faster; Silicon Valley types who use nootropics and other “smart drugs” not approved by the Food and Drug Administration to potentially increase their brain function; and people who try things like transcranial direct current stimulation, which uses low electrical currents applied to the head to stimulate neuron function.

One of Daley's slides suggested that "enhancements" are on the table. Image: George Daley

Lance Armstrong admitted to injecting himself with erythropoietin, a hormone that stimulates the production of red blood cells, to help him win the Tour de France. Daley said that it’d be possible to use CRISPR to make your stem cells naturally create more of the hormone.

“Why depend on injecting yourself with erythropoietin if you wanted to win the Tour de France?,” Daley said. “Why not just modify your hematopoietic stem cells to produce more erythropoietin?”

Considering how we’ve used every other medical technology for the arguably less “ethical” use of human enhancement, why wouldn’t transhumanists try out CRISPR—if it becomes available—to literally change their (or their unborn children’s) DNA to make them stronger, faster, smarter, or less disease-prone?

“We’re probably going to need new international oversight structures so that we don’t realize these dystopian Brave New World examples,” Daley said at the summit.

Should such uses of CRISPR be outlawed? Are they unethical? It’s hard to say—but bioethicists and regulators are concerned that a mutation or unsafe gene could be put into the human germline, meaning that it would be passed from generation to generation.

“We also need to regulate the specific uses of the products because we’re all concerned about off-label use,” Barbara Evans, director of the Center for Bioethics and Law at the University of Houston, said Wednesday.

More conservative voices from the bioethics community are advocating for a full ban on the technology, regardless of how it’s used. But just because some people want to use the technology in ways that so-called “bioconservatives” may not like, Daley says it’d be wrong for regulators dismiss CRISPR’s human potential.

“There are some who are going to say, ‘No we shouldn’t go through that exercise at all—the technology has no real legitimate uses, therefore we don’t have to worry, we just ban it,’” Daley said. “But I think we want a more nuanced argument than that. And that is, I think, what we’re trying to figure out here.”

TOPICS: gene editing, International Summit on Human Gene Editing, CRISPR,CRISPR/Cas9, Futures, genetics, news, transhumanism, zoltan istvan

Geneticists Are Concerned Transhumanists Will Use CRISPR on Themselves

Pereirano

Miembro habitual

- Mensajes

- 9.218

- Reacciones

- 3.459

Francisco Mojica, pionero de la técnica que reinventará la genética

“Estoy viviendo la revolución CRISPR con agobio y felicidad”

La nueva herramienta de edición del genoma se considera ya la gran panacea en el campo de la biología y la medicina. Un artículo en la revista ‘Cell’ titulado ‘Los héroes de CRISPR’ cuenta la historia de su descubrimiento desde sus orígenes en Alicante y rescata la figura de su iniciador, el microbiólogo Francisco Mojica. Abrumado por la atención que está recibiendo, este investigador, que nos confiesa que ni siquiera tiene móvil, se muestra humilde: “No creo que haya hecho tanto como para merecer esto. Yo solo hice lo que había que hacer en su momento”.

Hablamos con Francisco Mojica, el investigador de la Universidad de Alicante que dio los primeros pasos necesarios para la edición del genoma con la nueva herramienta CRISPR. / Roberto Ruiz / Sinc

El acrónimo CRISPR está revolucionando ya la biología y la medicina: es la llave para editar de forma sencilla y accesible casi cualquier rincón del genoma. Estas tijeras moleculares prometen revitalizar la terapia génica y revolucionar los tratamientos del cáncer o el sida. Incluso podría aplicarse para manipular la información genética de embriones humanos.

Las expectativas son tan amplias que se ha desatado una auténtica lucha por obtener los derechos de la patente. Dos de sus pioneras, Jennifer Doudna y Emmanuelle Charpentier, recibieron el Premio Princesa de Asturias de Investigación Científica y Técnica en 2015, y todas las quinielas apuntan a que tarde ganarán también el Nobel. Pero la historia no se limita a ellas. Bajo el nombre Los héroes de CRISPR, un reciente artículo publicado en la revista Cell por Eric Lander, director del Broad Institute del Instituto Tecnológico de Massachusetts (MIT), repasa la trayectoria de doce científicos claves en su desarrollo. Y el primero de ellos es Francisco Juan Martínez Mojica (Elche, 1963), ahora profesor de Microbiología en la Universidad de Alicante. Con él empezó todo.

El artículo ‘Los héroes de CRISPR’ lo reconoce internacionalmente como uno de los doce científicos claves en su desarrollo

La primera mención a CRISPR, que consiste en secuencias de ADN presentes en muchos microorganismos, tuvo lugar en 1987, cuando un grupo de investigación japonés las encontró por azar mientras descifraba el genoma de una de las bacterias más comunes. Sin embargo, apenas se les dio importancia.

Unos años después, el por entonces doctorando Mojica las volvió a encontrar mientras analizaba el genoma de la arquea Haloferax mediterranei, un microorganismo presente en las salinas de Alicante. Intrigado por su presencia, comenzó una serie de investigaciones que le llevaron a identificarlas en muchos otros organismos y a desentrañar su papel en la biología: son autovacunas microbianas, fragmentos de virus y otras partículas que se alojan en el genoma de las bacterias como una memoria de la infección. Él no lo sabía aún, pero estaba dando el primer paso de una nueva revolución.

¿Cómo se encontró por primera vez con las secuencias CRISPR?

Yo estaba haciendo mi tesis en una línea de investigación sobre modificaciones genéticas que provocaba la sal en ciertas regiones del genoma de la arquea. Esto alteraba el comportamiento de las proteínas que cortan ADN. Al estudiar una de estas regiones vimos que había unas secuencias espaciadas de forma regular. No sabíamos que existieran secuencias parecidas en ningún otro organismo, ni siquiera conocíamos el artículo del grupo de Japón. Por entonces no había internet, y el acceso a la información era mucho más complicado. Inmediatamente nos dimos cuenta de que lo que habíamos visto podía ser importante.

“Enviamos nuestro descubrimiento a cuatro grandes revistas científicas y todas nos lo rechazaron porque era tan tremendo que no podían creerlo”

¿Por qué pensaban que esas secuencias tenían que ser importantes?

¡Porque tenían muchísimas! Y estos microorganismos no se pueden permitir el lujo de tener ornamentos en su genoma. Todo lo que tienen está aprovechado.

Y además estaban presentes en muchos más microorganismos…

Sí, después vimos el artículo de los japoneses, que las encontraron en una bacteria intestinal. En los años siguientes se fueron publicando los genomas de más microorganismos y comprobamos que estaban presentes en muchos de ellos. En el año 2000 las definimos como una familia, y por entonces las llamamos SRSR, las siglas en inglés de “repeticiones cortas regularmente espaciadas”.

¿Cuándo descubrieron su función, que funcionaban como un sistema de defensa?

En el año 2003, en una de las secuencias vimos que había un fragmento de un fago, un virus que infecta bacterias. Entonces volví a buscar en todas las secuencias disponibles y encontré fragmentos así en muchas más.

Y de ahí el periplo para intentar publicarlo. Lo mandaron a varias de las revistas más importantes, sin éxito. ¿Por qué?

Sí, lo mandamos a cuatro de las revistas más importantes, incluida Nature, pero lo rechazaron en todas. Los comentarios de los revisores y los editores eran muy negativos. Era algo tan tremendo que les costaba mucho creérselo. Unos decían que necesitábamos demostrarlo con más experimentos, otros nos dijeron que no era original, que ya se había descrito antes. Yo protesté diciendo que era algo muy grande y que no se había descrito nunca, pero me dijeron que no interesaba para la revista.

Al final se publicó en el Journal of Molecular Evolution, una revista muy poco importante.

Sí, llegó un momento en que estábamos muy desencantados, y pensamos que lo que teníamos era demasiado importante como para dejarlo en un cajón. Siete años más tarde, uno de los revisores que nos rechazó el artículo me pidió perdón, me dijo: “Lo siento pero, sinceramente, es que no me lo podía creer”.

Así funciona CRISPR. Infografía: J. A. Peñas

¿Podía intuirse en aquel momento su posible aplicación como una herramienta de corta-pega genético?

No. Se sabía que funcionaban como un sistema de interferencia, pero no cómo ocurría ese mecanismo: el corte de ADN que rompe a los virus y que a su vez permite la edición del genoma. Para lo que sirvió fue para llamar la atención de la comunidad científica. Un campo que estaba muerto despertó, haciendo que muchos grupos se interesaran por él hasta llegar a comprender su mecanismo y desarrollar las aplicaciones.

¿Cuál fue el punto de inflexión para llegar a la revolución que supone CRISPR?

Para mí, fue en 2011, cuando el grupo de Virginijus Siksnys, de Lituania, demostró que podía transferirse el sistema de una bacteria a otra radicalmente diferente, y que funcionaba. Eso probaba que podía usarse porque era activo en otros huéspedes. Los microbiólogos tenemos claro que ese fue un trabajo fundamental.

Usted también es responsable del nombre CRISPR, aunque en un primer momento las llamó de forma diferente. ¿Cómo surge el nuevo término?

Sí, nosotros las habíamos llamado SRSR. Pero poco después un grupo en Holanda las definió con el acrónimo SPIDER. Entonces contactaron conmigo para ver si nos poníamos de acuerdo en un nombre común. Yo les di varias opciones, incluida la de CRISPR, que fue la que se escogió porque era la más completa: corresponde a las siglas en inglés de “repeticiones cortas agrupadas regularmente y separadas en forma de palíndromo”.

Ahora ese nombre promete mover miles de millones de euros. Hay una disputa por los derechos de la patente entre los laboratorios de Douda y Charpentier, que fueron quienes abrieron el camino a la edición genómica, y el de Zhang en el MIT, que diseñó la forma de usarla en humanos. ¿Qué opina sobre la posibilidad de patentar una técnica así?